It goes without saying that a film’s sound is an essential element of its overall success. And yet, it so often remains unnoticed by critics and audiences alike. But every so often, a film will come along where sound becomes an integral part of the storytelling. In this new column, In The Mix, we will take a closer look at these films and delve into the mechanics of how and why sound – from the mix to the score – is such an important part of the cinema experience.

Here, Kaleem Aftab speaks with Oscar-winning sound designer, Nicolas Becker, about his approach to the sound design of Sound of Metal.

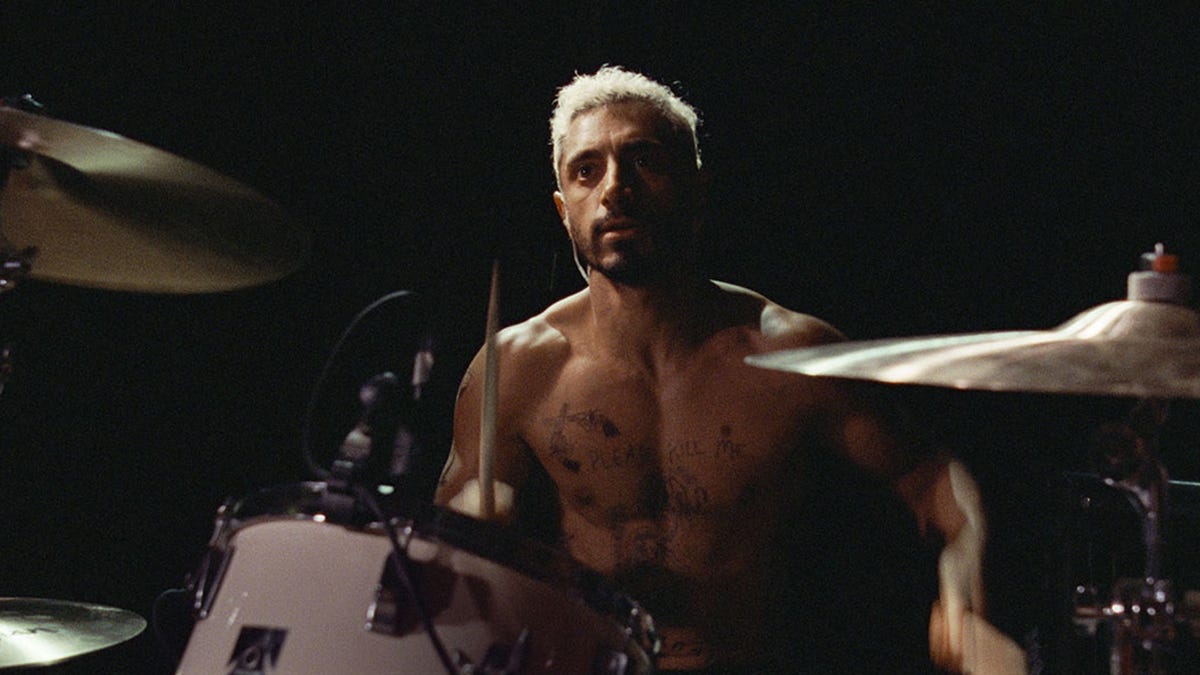

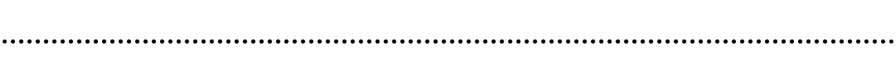

In Darius Marder’s directorial debut, which he co-wrote with his brother Abraham (who also co-wrote the film’s score), Riz Ahmed plays Ruben, a heavy-metal drummer in a relationship with his band’s lead singer, Lou (played by Olivia Cooke). Both their personal and professional lives unravel when Ruben starts to lose his hearing. Struggling to accept his deafness, even after he joins a deaf community in search of support, Ruben is drawn to the possibility of advances in medical research and treatment in restoring some semblance of hearing. It is a film that relies heavily on a complex sound design, devised by prolific foley artist, supervising sound editor and sound designer Nicolas Becker.

Sound of Metal (2021)

'It was so strange receiving the Academy Award on a roof of a studio in Paris,' says Becker, who won the Best Sound Oscar for his supersonic work on Sound of Metal. (the film also received an award for Best Editing and Becker co-composed the score.) 'So winning seems not real. I think getting an Oscar is unreal in any case, but to receive it in such conditions makes it even more unreal.'

The irony, of course, is that Becker is a master of making the unreal real, creating sounds that mimic reality and fool us into believing that the fiction we're witnessing onscreen is reality captured. Before Sound of Metal, Becker was most-lauded for his remarkable work as a foley artist on Alfonso Cuaron's 2013 space opera Gravity. In space, you are in a vacuum, where sound cannot be transmitted. So Becker focussed on the ability of sound to be transmitted through the interaction of elements, meaning that when characters grabbed and touched anything, the resulting vibrations would travel into their ears, delivering a muffled representation of that sound. Consequently, all the foley – mimicking the loosening of bolts, the opening of doors – was done through transducer recordings, which record vibrations rather than regular airborne audio. The incredible layers of sound effects in Gravity come from those recordings. Becker would expand on this work for Sound of Metal.

Sound of Metal (2021)

Becker also used ‘embodied’ sounds while working on Danny Boyle's 127 Hours (2010). Who can forget the experience of hearing Aron Ralston (James Franco) sawing his own arm off? And for Andrea Arnold’s American Honey (2016) and Wuthering Heights (2011) he created supernaturalist sound design. The range and breadth of his work, as well as his unique approach to creating soundscapes, ensured that Becker was at the top of the list when it came to Darius Marder seeking a sound supervisor for his directorial debut. Marder wanted the audience to understand what hearing loss is like for someone experiencing it – which is far from the sound of silence. As a result, we hear an approximation of Ruben’s own experience: there is tinnitus and rapid decline. And the expensive cochlear implants that he hopes will solve all his problems prove to be no miracle cure. We hear unbearable, scraping metallic sounds as his ears try to adjust, to no avail.

Even though he knew that his budget was far from the scale of Gravity’s, Marder’s ambitions were no less grand, and he approached Becker to collaborate with him on Sound of Metal. Becker explains why the challenge posed by the filmmaker appealed to him: ‘There's always this idea that if you want to do good work on a film, you need a lot of money,’ says Becker, ‘So for me, it was super important to show that you can achieve great things without a crazy budget and what is important is the fact that the film has been written and conceived in a way that considers sound. When you start to write, if you integrate sound as a part of the script, you can achieve great things without big scale stuff.’

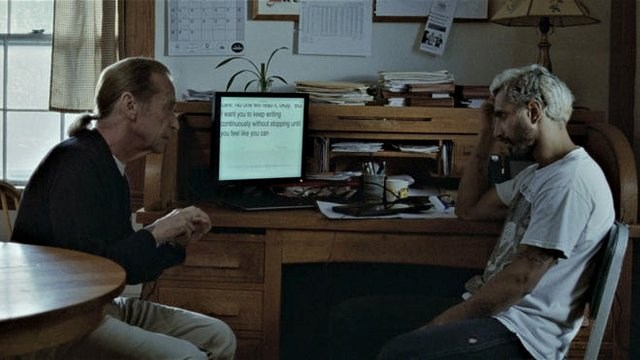

Sound of Metal (2021)

As part of the courting process, Marder visited Becker in Paris. But before he met with him, Marder had devised a low-frequency concept for the sound design, which fit his desire to have the sound design weave in and out of the film’s diegesis. One of the first things Becker did was take Marder to the soundless anechoic chamber of the Institute de Recherche et de Coordination Acoustique/Musique (ACRAM), an echo-free room designed to absorb sound and electromagnetic waves. 'When you go into that kind of anechoic chamber, it's a shock because you realise that if you remove all the sounds, there is still your own sound,' explains Becker. 'There is a sound that you actually create, which is your heartbeat, the sound of your tendons, the blood pressure; when you speak, you understand that your whole body vibrates – you are a big instrument, it's not only a small tube, it's like a double bass.'

Sound of Metal (2021)

This moment between the duo heavily informed the sound design for the film. Becker wound up miking Ahmed with stethoscopic microphones, placing them inside the actor’s mouth and throat. They recorded his heartbeat, his pulse, and all the sounds of his body. The result is incredibly atmospheric. And if you watch the film in an Atmos-equipped or surround-sound cinema, the audio will feel like it’s dancing around you.

'We spent a lot of time before the shoot to record [sound for] the film,' adds Becker. 'I came during the shoot to record a lot of the sound, to record the concert that we see at the start of the film. I really like to listen to the voice of the actor with my own ears, to listen to the atmosphere, to feel what is right, and to kind of memorise these things.'

Sound of Metal (2021)

According to Becker, recording voices and outputting them is one of the most challenging things to get right. 'Voice is very tricky,' he notes. 'It's the most complex sound. A lot of people, when they start to clean voices in the studio, they transform the voice and a lot of time the process loses the life from the voice. I think to listen to the voice properly, with your real ears, those imperfections are what makes voices unique. I had to think about what is the characteristic of the voice of Riz, and in that way, you can keep everything from his voice while removing some problems which are not coming from his voice. Sometimes people think "he has a weird frequency here" and they take that frequency away, but then there is no life in it.'

Sound of Metal (2021)

The film’s narrative is divided into two distinctive sonic parts, the first of which reflects Ruben’s life as a drummer, which is loud, gritty and full of sound. The second part is much quieter as Ruben comes to terms with his deafness and what he goes through – both physically and mentally – in the wake of it. To achieve this distinction, Becker used two different recording studios in post-production. ‘For the first part, I called a friend, Mario Caldato Jr., who used to work with the Beastie Boys. He has an amazing studio house in L.A. It's always full of musicians and we said “It would be nice if you can find two rooms for us”. He then transformed those into the editing rooms. For the second part, I proposed [we] go to a facility owned by the director Carlos Reygades in Mexico, in the middle of the mountains… I have a feeling, with this kind of film, you have to do that – you have to be as close to what you are relaying as possible. In the same way that Riz learned sign language and to play the drums, we had to feel the energy, have the experience.’

Sound of Metal (2021)

Becker has two theories as to why he's so obsessed with sound: ‘My parents were teachers, and they didn't allow us to watch a lot of films. Sometimes, when they were watching a film, I would try to see the film through the keyhole to the room, and I could see the picture, and I couldn't really hear the sound. So maybe it's coming from the frustration of just being able to see and not being able to hear. The other theory is that when I was 13, I saw a documentary on how you make a film for kids… there was one part specifically about sound. It was [a] shot of a rusty boat lying on a beach and they showed the scene where, one time, you could hear the seagulls, the next time, just the waves, and another time with kids playing. And then with music, and finally everything together. I was like, Wow. I remember every second of this thing. It blew my mind.’

And now this talented, BAFTA and Oscar-winning artist is blowing our minds with his approach to sound. He is transforming the cinema experience one eardrum at a time with a film that is made to be seen, and heard, in the theatre.

Sound of Metal is now showing in cinemas.