Nicole Davis speaks to filmmaker Bianca Stigter about her extraordinary documentary.

It began on Facebook. While a place not usually associated with productivity and inspiration, it’s where historian, author, critic and now filmmaker Bianca Stigter first encountered the footage that would become the basis for her extraordinary documentary Three Minutes: A Lengthening. The post concerned Glenn Kurtz’s book Three Minutes in Poland: Discovering a Lost World in a 1938 Family Film, detailing his own discovery of a three-minute home movie, shot during a family trip to Europe in 1938, just prior to the beginning of WWII. The amateur footage was taken by his grandfather David Kurtz, who had emigrated to America as a boy, and depicts the people of his hometown of Nasielsk, Poland. The small town, situated north of Warsaw, had a population of roughly 7000 people, an estimated half of which were Jewish. By the end of the war, only a hundred of Nasielsk’s Jews had survived the Holocaust.

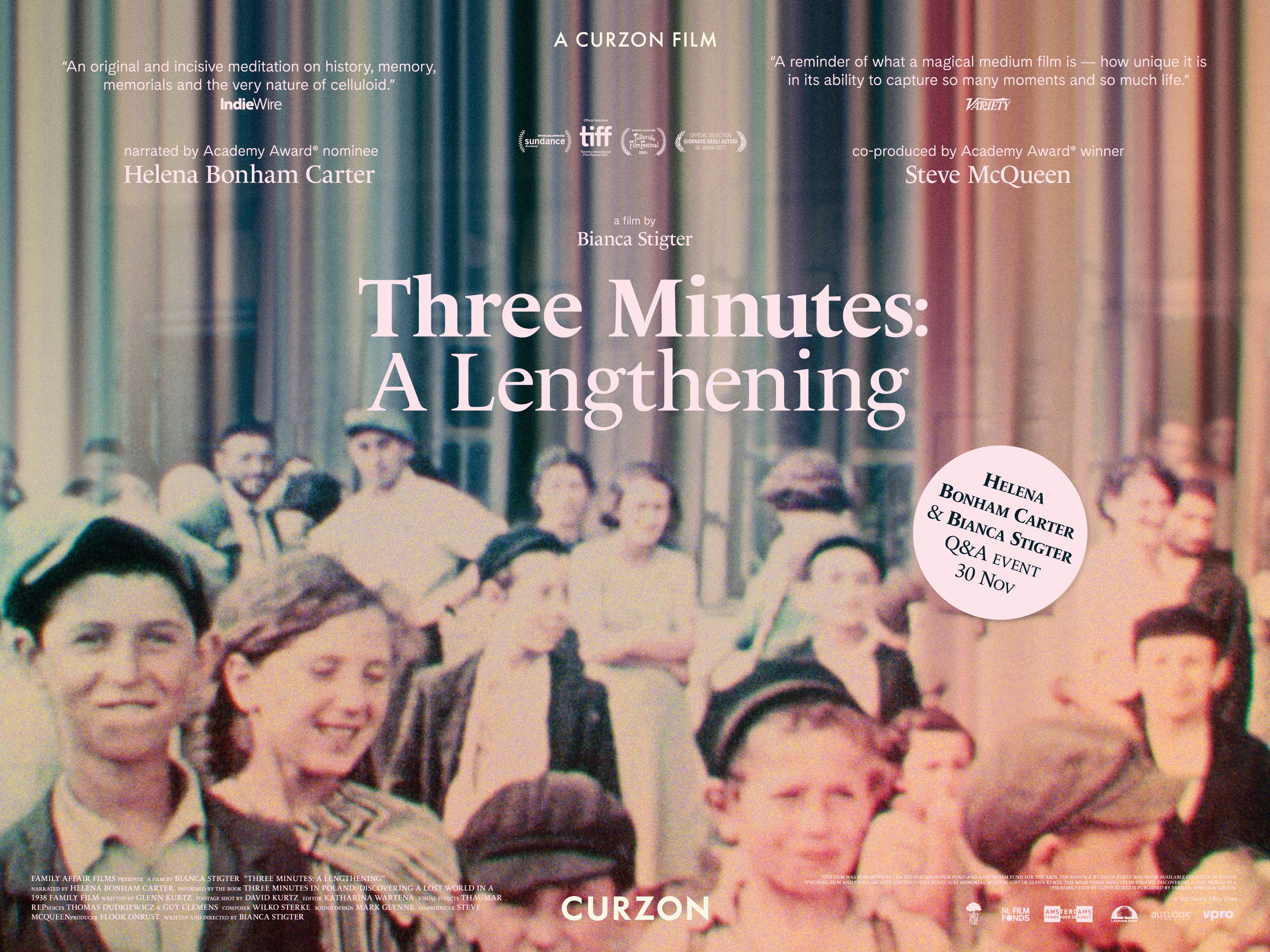

Three Minutes: A Lengthening (2022)

Stigter quickly sought the footage on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s website. ‘I was fascinated by it immediately. I felt this historical sensation of closeness,’ she remembers, ‘because it's in colour, which is, of course, very rare for material from that time. We tend to think that things in the 1930s happened in black and white. But this felt contemporary.’ With the historical hindsight of knowing what happens to the people in the footage only a year later, Stigter explains that she felt two urges. The first, she says, was to shout at the screen for them to escape, to run away. But then came the second: ‘You have all these conflicting ideas and emotions when you see it for the first time,’ Stigter continues, ‘I had the urge to make it last.’

At the time she discovered the footage Stigter wasn’t working as a filmmaker, so her first idea was to read Glenn Kurtz’s book. But when the International Film Festival Rotterdam got in touch with an opportunity to make a video essay as part of their Critics’ Choice strand, she knew it was her chance to work with the material and reached out to Kurtz. Together they developed a short version of the film that screened as part of the festival. However, Stigter felt as though there was a lot more that could still be done with the footage.

It’s an instinct that proved true. Just shy of 70 minutes, Three Minutes: A Lengthening is a forensic examination of David Kurtz’s film, containing and pursuing many lines of questioning. How did this footage come to be? What effect did the camera’s presence have on who we see in it? What time of day is it? Who did that grocery store belong to? ‘Why a lengthening?’ I asked Stigter. Not a deepening, widening or any other signifier of expansion. ‘Because my main goal was to make it longer,’ she states, ‘To spend time with it. It’s kind of a detective story and I wanted to make the audience part of that story so that you get acquainted with history in a different way than by reading a book or seeing a generic documentary.’ One of the strengths of the film is how the filmmaker illuminates, enlivens and makes cinematic what history is. As she rightly says, it’s detective work, and her film holds a magnifying glass up to this moment in time, teasing out all of its clues and curiosities. And the investigation is guided by the voice of Helena Bonham Carter.

Three Minutes: A Lengthening (2022)

Stigter cites historical imagination as the reason for this filmmaking approach. She recalls a trip she took as a student to then-communist Prague. She remembers how the version of historic events presented to them ‘differed from what we learnt in the West,’ notes Stigter. It was a small moment of epiphany that history is malleable and biased. Subsequently, Stigter’s film never presumes to know more than its audience, rather it preserves the unmediated and authentic quality of the footage and invites us into a version of history that Stigter feels is ‘more vivid and close to you, and connected to the present.’

Given how close the footage was to being lost forever to damage and decay, as Bonham Carter’s narration tells us, the film feels all the more valuable and actually details the restoration process; how a colour lab treated the effects of vinegar syndrome, edge weave, buckling and crazing. ‘I thought it was good to be aware of how it’s actually possible that we get to see this world,’ says Stigter, ‘and how lucky we are that it could be restored.’

Stigter also feels fortunate that she and Glenn Kurtz were able to speak to Maurice Chandler, a survivor of the Holocaust in his late 90s who was born in Nasielsk and features in the footage, thus adding another level of intimacy. ‘It’s his past. He knows what happens outside of the frame and could bring it to life even more,’ says Stigter. ‘He had these fantastic stories about buttons [owing to a button factory located in Nasielsk, at which many of the town’s residents were employed] and these stories of joy. He was very happy,’ Stigter tells me. For her, this became important to include: ‘It’s not only a story about violence and misery, but also a story about what [came] before.’

After such an incomprehensible time in history, Stigter wanted to focus on what ‘happened to all these individuals and have a memorial to them.’ There is a sequence in the film where all of the faces are cut out and pasted onto the screen one by one, no matter how blurry or grainy. You don’t quite realise how many people have passed through the frame until Stigter invites you to look at everyone single one of them. In most instances, she says, ‘this is the last trace we have [of these people], so even if we can’t put names to them, we can remember and acknowledge their faces.’

Three Minutes: A Lengthening (2022)

Stigter knew she wanted to end the film by showing the footage in its entirety again. ‘You look at it in a different way, because you recognise people you’ve become acquainted with,’ she notes, and in continuing to play David Kurtz’s footage from a trip to Switzerland, there is a defiant sense of ‘life going on.’ The life of the film itself has gone on too. It had its premiere at the Venice Film Festival in 2021. ‘It’s still being shown all over the world,’ marvels Stigter, ‘Every time I see it on a big screen I see so much more detail. Still, there are new things!’

Many people might have scrolled past that Facebook post, but thanks to Stigter, we have a documentary that asks us not only to look, but to look again, and again. And in looking, we see not just new details, but new evidence of life. That, to Stigter, is the strangest and most beautiful thing about the footage. ‘The Nazis set out to completely erase a people and culture, and yet, here we have this thing [that exists in protest of that].’

Three Minutes: A Lengthening is now in cinemas and on Curzon Home Cinema