As the new documentary Loving Highsmith offers only the briefest of nods to its subject’s history of racism and anti-semitism, Anna Bogutskaya asks: how can we celebrate talented artists without smoothing over their contradictions?

Patricia Highsmith wrote 22 novels, eight short-story collections, and thousands of pages of diary entries and journals. She also wrote dozens of letters of vitriolic, hateful, racist and anti-semitic bile. The documentary Loving Highsmith – dedicated to the lesser known, romantic and desirous life of the acclaimed writer – swiftly disposes of this side of her, saying towards the end: ‘By now Highsmith makes fewer and fewer entries in her diaries. And they start to contain rants and prejudice against Jews, Arabs and Blacks.’ That’s it. A pair of sentences used to address a lifetime of bigotry.

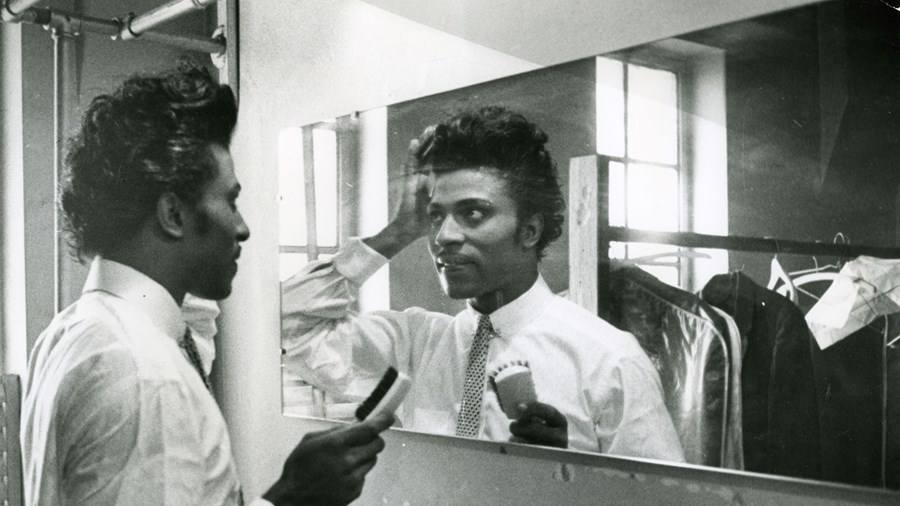

A profound difficulty looms over Loving Highsmith, a new documentary about the emotional life of the famed writer: what do we do with the problematic parts of great personalities? What’s more, should outsized talent be celebrated at all costs? Can we honour the talent without ignoring the problematic, or even monstrous, aspects of so-called geniuses? Eva Vitija’s film is one of several recent documentaries that addresses these questions. Roger Ross Williams’ and Brooklyn Sudano’s Love to Love You, Donna Summer (2023) has to reckon with the disco pioneer’s late-career comments about homosexuality and the AIDS crisis that were perceived as anti-gay. And Lisa Cortés’ Little Richard: I Am Everything (2023) skirts around the rock star’s conflicted and contradictory relationship with his own sexuality, and his loud homophobia in his later years.

Little Richard: I Am Everything (2023)

Immense talent often brings immense contradictions. It’s a daunting task for any single documentary to try and address them all. But is ignoring it wholesale the only way to navigate it? In her upcoming book-length essay Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, writer Claire Dederer uses the metaphor of the stain to describe the unease we feel when we love the work, but cannot love the author. The more we know about an anointed genius and their problematic views or life, the more destructive the stain becomes. As Dederer writes: ‘The more closely we are tied to the artist, the more we draw our identity from them and their art, the more collapsed the distance between us and them, the more likely we are to lose pieces of ourselves when the stain starts to spread.’

Highsmith’s talent has never been in question. Her stories, often of the murderous type, explored themes of violence, insanity and festering secrets (also known as: the good stuff). She started writing what she called her ‘creepy ideas’ when she was a teenager. Her very first novel, Strangers on a Train (1950), was adapted by Alfred Hitchcock a mere year after publication. Highsmith’s work has been consistently brought to the screen by filmmakers worldwide, including Claude Chabrol (The Cry of the Owl, 1987), Wim Wenders (The American Friend, 1977), Todd Haynes (Carol, 2015) and, most recently, Adrian Lyne in the un-erotic drama Deep Water (2022).

The American Friend (1977)

The greatest product of her dark imagination, the refined serial killer and con artist Tom Ripley, has been played by five different actors (soon to be six, with Andrew Scott set to portray him in an upcoming limited series): Alain Delon in Purple Noon (1960), Dennis Hopper in The American Friend (1977), Matt Damon in The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999), John Malkovich in Ripley’s Game (2002) and Barry Pepper in Ripley Under Ground (2005). ‘There isn’t any constant personality for the writer,’ Highsmith wrote in her diaries. Ripley, who steals identities and takes on his victims’ faces, was, in this way, Highsmith’s alter-ego. Sometimes, she even signed off her letters as Ripley.

The director of Loving Highsmith was drawn at first to the work, the darkness of Highsmith’s stories and her sharp sentences. But it was Highsmith’s unpublished diaries that made her, as she explains in the film’s voiceover, ‘fall in love with her’. Recently published in an edited tome of a springy 1,024 pages, Highsmith’s diaries are a smorgasbord of extreme feeling, passages of longing and writerly ambition. Like many emo-leaning writers before and after her, Highsmith set herself apart from others with her talent and depth of feeling. ‘I put my trust in my intensity – my enormous need – which I do not see at all in them,’ she wrote.

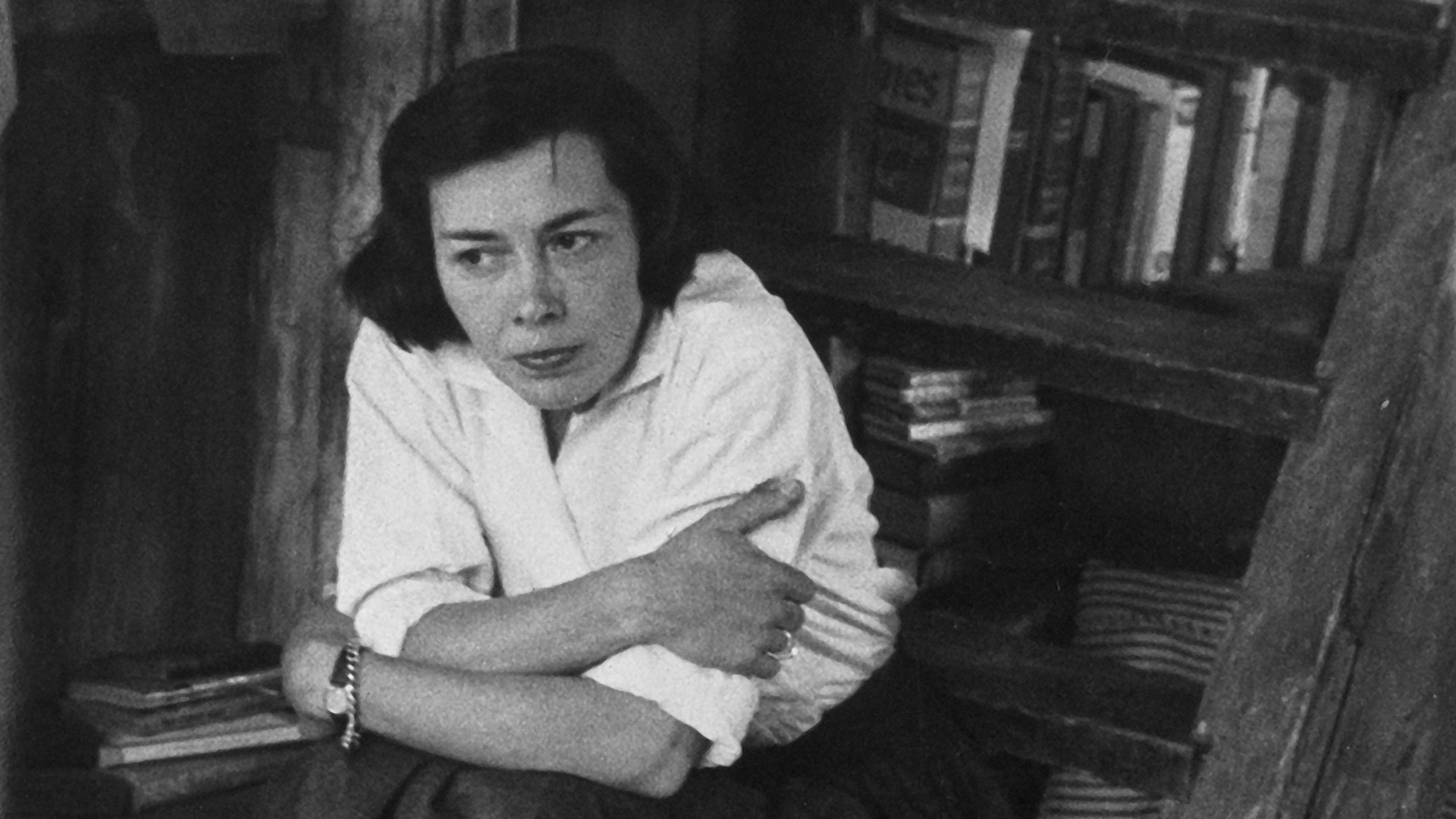

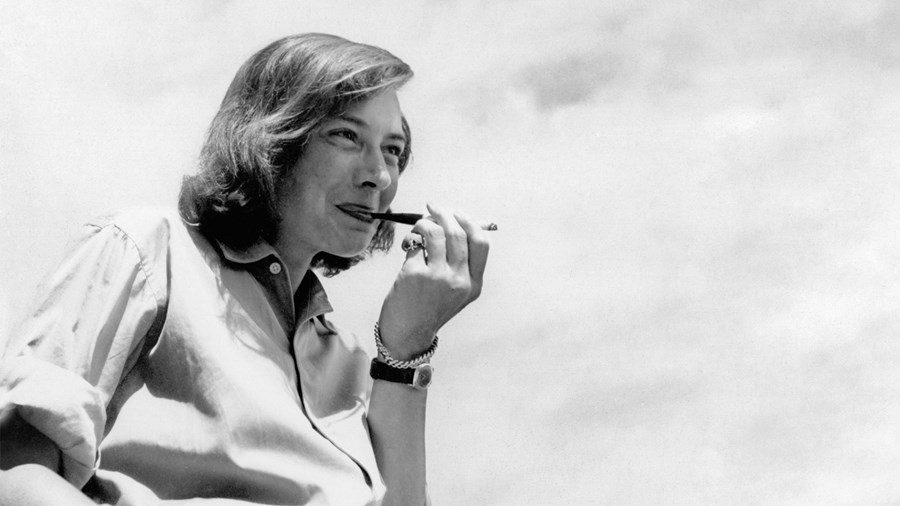

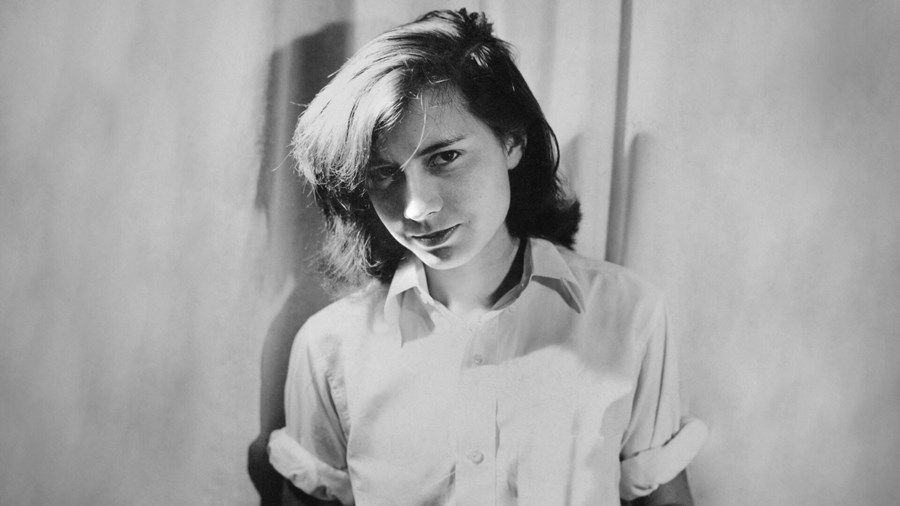

Loving Highsmith (2022)

It’s hard not to fall in love with these words, and with Highsmith, if you look at her work alone and the selected passages from her diaries, which are narrated in the documentary by Gwendoline Christie. She is intense, needy and lovelorn, with a deep void left by a relentless, cruel mother who took pleasure in withholding love and approval from her only daughter. A romantic all her life, Highsmith fell in love and lust often, and hard.

She was also, notoriously, a spiteful character. Even her publisher once described her as ‘mean, cruel, hard, unlovable, unloving human being’. Highsmith was not unaware of it. ‘I live my life backwards,’ she wrote, ‘My envy turned to hatred and my hatred to contempt.’ We know she hated a lot of things and a lot of people, but she also loved. Secretly, passionately, violently.

Loving Highsmith (2022)

Already a well-known writer, in gay bars she was rumoured to be ‘Claire Morgan’, the pseudonymous author of The Price of Salt (later republished as Carol), then the only lesbian novel with a happy ending (much later adapted into the sapphic erotic drama with Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara). Only her second book, Carol emerged almost fully formed from a chance encounter with a woman in a department store; Highsmith plotted out the book in one evening in scrawls in her notebook. Even though she only saw that woman once, Carol came to her, as she wrote in her diaries, ‘from her own bones’.

What to do, then, with a problematic talent? Two sentences to swat away her lifelong bigotry seems like an insult, but so is syphoning a talent like hers, a queer woman’s life and loves. It’s because we love something that we demand it to be better. And contemporary documentaries should be informed by the contradictions of loving a talent like Patricia Highsmith. Covering up the stain doesn’t wash it away.

WATCH LOVING HIGHSMITH IN CINEMAS OR ON CURZON HOME CINEMA