As Flux Gourmet plays in cinemas and on Curzon Home Cinema, Ian Haydn Smith journeys through filmmaker Peter Strickland’s singular body of work.

There is a unique relationship between the images we see and sounds we hear in Peter Strickland’s films. Sound design is a key element of any film, but in Strickland’s work, it is frequently taken to extremes. In the case of his second feature, Berberian Sound Studio (2012), the creation of sound is integral to its narrative. Toby Jones’ protagonist, Gilderoy, is a foley artist employed on a 1970s Italian horror film and whose immersion in his work finds him unable to distinguish reality from the fictional worlds helps create. By accentuating the everyday sounds – making the banal threatening – Strickland achieves an air of menace.

Strickland’s cinema employs an aural landscape in a fascinating way; sound and music don’t drive narrative momentum in any conventional way. They are employed as a catalyst of creation, forming a mutual relationship with a succession of images that edges towards the abstract. It’s an approach that pays off handsomely in Flux Gourmet.

Strickland’s fifth feature is a memoir of sorts. Not in the vein of recent biopics of Elton John and Freddie Mercury, the director has noted, but more in the style of Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir – drawing on personal experiences to explore specific themes. In the 1990s, Strickland was a founder member of The Sonic Catering Band. They operated like the band headed by Fatma Mohamad’s Elle di Elle in Flux Gourmet, ‘taking the raw sounds recorded from the cooking and preparing of a meal and treating them through processing, cutting, mixing and layering’.

Flux Gourmet (2022)

As The Sonic Catering Band’s website notes, their remit was ‘to plough and furrow as meticulously as possible every possibility inherent in the cooking process, both aurally and conceptually, within a shelf-life of around five years. In terms of personnel, The Sonic Catering Band would be an anonymous unit of whoever happened to be around. For the first year, it definitely had the feel of a loose collective with various characters drifting in and out.’ Strickland achieves the same composition and aims with his on-screen musical collective. Mohamad works with Ariane Labed and Asa Butterfield’s co-composers/creators, but there is an air of impermanence about the group; beyond their personal differences, their performances feel like one-off experiences, with each possibly being the last.

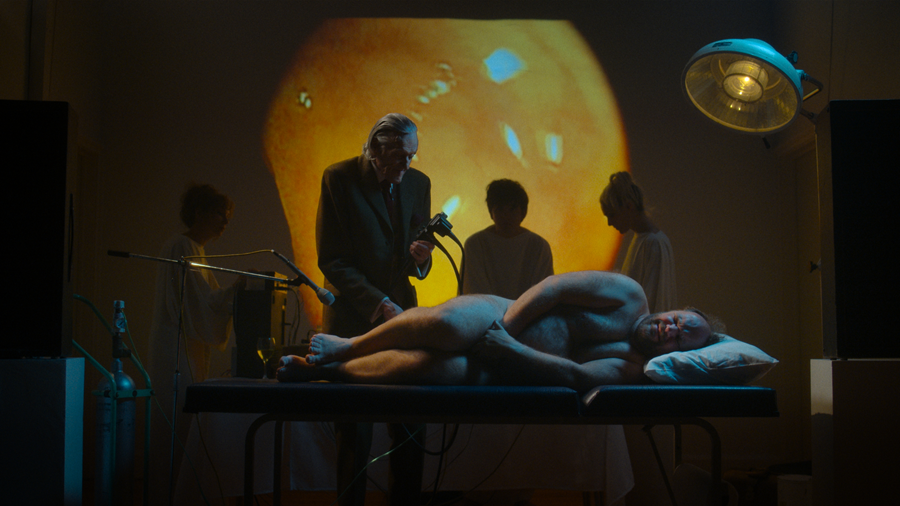

But the aural landscape in Flux Gourmet, as in Berberian Sound Studio, is everything. Beyond the cooking, Strickland details the personal sounds of the human body, bypassing frat-boy humour in grappling with one of the character’s ailments. Flatulence, for the aptly named Stones (Makis Papadimitriou), not only causes him discomfort, but extreme social embarrassment. An examination of him by the eccentric doctor (Richard Bremmer) housed at the Sonic Catering Institute, which is run by Gwendoline Christie’s arts benefactor (Strickland’s wickedly sly dig at the institutionalised altruism of arts funding organisations), is presented as a baroque performance piece, the misé en scene appearing to owe as much to the tableaux of Peter Greenaway’s work as it is Strickland’s own fervid imagination.

Flux Gourmet (2022)

The notion of taboo is a continuing theme in Strickland's work. In Berberian Sound Studio, it was explored through the extreme violence of the horror genre. Although we see little of it on the screen – Strickland has spoken about how averse he is to the actual representation of violence – it is an undercurrent in the film, adding to Gilderoy’s increasing sense of paranoia and threat. Violence is also central to Strickland’s feature debut, Katalin Varga (2009), which offers a novel spin on the rape-revenge film. Previous entries in this sub-genre, from Death Wish (1974) I Spit on Your Grave (1978) and Ms. 45 (1981) to Irréversible (2002) and Revenge (2017), often detail the violent act that starts the narrative. Strickland’s film is more oblique, which in turn affects the tone of the film. For the most part, Katalin Varga is a pastoral journey through the Romanian countryside, accompanying Hilda Péter’s titular character, along with her son Orbán (Norbet Tankó) as she hunts down the two men responsible for the crime. Once again, sound is key. The film won an Outstanding Artistic Contribution award for its sound design at the Berlin Film festival and it's one of the few films since Aleksandr Sokurov’s extraordinary Mother and Son (1997) to capture the sound of nature as evocatively.

Katalin Varga (2009)

Nature also plays a key role in Strickland’s third feature, The Duke of Burgundy. Like Berberian Sound Studio, it looks back to a particular kind of European cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. In this case, films that dabbled in softcore pornography while hewing close to the aesthetics of the arthouse cinema of the era. However, although Strickland is as knowledgeable of and immersed in these worlds as he is in experimental music, The Duke of Burgundy is never constrained by the trappings of pastiche, instead immersing his audience in an affecting relationship between Sidse Babett Knudsen and Chiara D'Anna's lovers, Cynthia and Evelyn. The nature of their sado-masochistic relationship develops, as the lines between dominance and submissions shift, or – more to the point – we become increasingly attuned to the complexities of their games and how the balance of power in personal relationships is never easily defined.

The Duke of Burgundy (2014)

Colour is also key to the film. There is a softness to The Duke of Burgundy that contrasts with Strickland’s subsequent work. (Around this time, he also worked with Icelandic artist/songwriter/performer Björk, directing the visually ravishing concert film Björk: Biophilia Live.) In Fabric, which plays out like a cross between the classic 1945 Ealing horror portmanteau Dead of Night, Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (1948) and classic Giallo (a particular kind of Italian horror spanning the 1960s through to the 1980s and defined by films like Dario Argento’s Deep Red [1975] and his original 1977 version of Suspiria) is all hard angles to The Duke of Burgundy’s soft edges. If the contrasting colours of his delightfully twisted sapphic romance are complimentary – a world where even the abject has a natural place within the colour scheme devised by Strickland and cinematographer Nicholas D. Knowland – Strickland’s tale of the fate that befalls owners of a demonically possessed red dress is defined by the boldness of its colour scheme.

In Fabric (2018)

In Fabric also features another key element of Strickland's work – his febrile imagination. His films work because Strickland doesn’t so much conceive of a storyline as conjures up an entire world. In Fabric isn’t just the story of a demonically possessed dress and the fate of all those who step into it. The department store selling the dress has its own bizarre history.

In creating a wider world in which his characters exist, Strickland employs a logic specific to it that ensures no matter how outlandish his characters’ exploits are, they make sense within that world. From Gilderoy’s increasingly fractured perspective on life in Berberian Sound Studio and Cynthia’s growing paranoia in Duke of Burgundy to Elle di Elle’s wild antics in Flux Gourmet, Strickland wholly immerses us in his worlds. And the experience can be as unsettling as it is exhilarating.

In Fabric (2018)

Flux Gourmet is now in cinemas and on curzon home cinema