Cinemas in the UK will soon reopen. Curzon venues around the country will welcome audiences back to their cafes and screens. It also sees the launch of the Curzon Journal, a hub for news, reviews, articles, interviews and much, much more. But what it is that draws us to the screen? Ian Haydn Smith explores cinema’s past, present and possible future, finding that the medium has always existed in a constant state of flux.

What is cinema? The question is the title of two volumes of collected writings by André Bazin, one of the founders of the influential French film journal Cahiers du Cinéma and the ideologue behind the French New Wave. With essays on Charles Chaplin, the Western, styles of editing, Italian Neorealism, stars and the nature of cinematic language, the books’ title engages with the form of the medium—what we see when we watch a film. Today, that question applies equally to how we watch, because the two decades has seen as much emphasis on the delivery of the medium as the message itself. (A shift that would have delighted mid-20th century cultural theorist Marshall McLuhan, whose ‘The medium is the message’ has transformed from a chapter heading to a mantra.)

But how did we get to this point?

And then there was light…

Take 1: INT. Salon Indien du Grand Café. Paris. December 1895

Officially it began here, just after Christmas, with the first public screening of the Lumière brothers’ collection of ‘actuality’ films. Ten single-shot shorts that capture daily life, with a total running time of less than eight minutes, are screened to a rapt audience.

Take 2: INT. Society for the Development of the National Industry. Paris. March 1895

The same films had actually been screened some nine months before, to an invited audience. Amongst them was Léon Gaumont, soon to be one of the first major film producers, and his assistant Alice Guy, who would become the first female filmmaker.

Take 3: INT. Wintergarten Music Hall. Berlin. November 1895

Max Skladanowsky and his brother Emil, stage a three-hour show at the famed Berlin venue, during which they screen over a minute (eight shorts) of film footage to audiences.

Take 4: EXT. Garden. Roundhay. October 1888

A family gather together in a garden of a house in a Leeds suburb. A brief snippet of this meeting, lasting barely two seconds, is filmed by French scientist, engineer and inventor Louis Le Prince.

So, when did cinema actually begin? The term was first used in the early years of the 20th century. Before that people talked about the ‘cinematograph’. What we regard as ‘cinema’ today—moving images projected onto or through a screen—was the product of experiments by the likes of Le Prince, the Skladanowskys and Lumières, along with Thomas Edison, Cecil Hepworth, Eadweard Muybridge, Birt Acres, William Friese-Greene, R.W. Paul and many more.

If taken more loosely, the moving image had been with us for far longer. In the 19th century, it was represented by a multitude of eccentrically named devices, from the Fantoscope and Zoetrope to the Phenakistoscope and praxinoscope. Before those, there was the magic lantern. The camera obscura is arguably the first moving image instrument, its combination of mirrors and lenses projecting images onto a blank wall. But such a device existed, albeit in rudimentary form, in nature. A crack in a cave might allow enough light in to project onto a wall what is outside it. This goes some way to explaining the existence of cave paintings that date back over 25,000 years.

A Cinematograph

No sooner had news of the Lumière’s screening spread—and their own tour set out across Europe and the world—than other inventors set about creating their own cinematographs. (The Lumières might have helped start something, but they had little faith in it—they refused to sell the design of their equipment and returned to making still cameras, noting ‘the cinema is an invention without any future’.) Within a few years, these minute-long shorts had expanded in length. With the integration of storytelling, they soon resembled the films we watch today.

With storytelling came the introduction of editing, which collapsed space and time. A film could give the illusion of the passage of time and could shift action from one scene to another. By placing the camera on a car, a train or its own mode of transport (what became known as a ‘dolly’) a filmmaker could create movement, which in turn affected pace. Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery and Life of An American Fireman (both 1903) showed what could be done with editing and movement. While in France, the magical worlds of Georges Méliès, creating illusions through editing and designing fabulous sets that allowed him to travel to the Moon or the bottom of an ocean, added mystery and wonder into the mix.

The Great Train Robbery (1903)

The ‘Biograph Girl’ Florence Lawrence and French comedian Max Linder became recognisable faces on the screen and through them, the notion of the star was born. Prior to this, actors were nameless characters on the screen. The spectacle of the moving image had been enough to entice audiences. But with stars, nascent production companies and the earliest film studios realised that a recognisable face could bring audiences back time and again to a screening.

By the early 1910s, the feature film was introduced. The first known feature, The Story of the Kelly Gang had been made in Australia in 1906. But it was in the 1910s that the potential profitability of a longer length film was acknowledged. And with it, studios became the dominant producers of films. Hollywood, which was a dusty town on the outskirts of Los Angeles at the start of the 20th century, by the 1920s had become the epicentre of the global film business.

The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906)

With industry came art. Film was an expensive medium and the scale of films being produced could bankrupt a studio if they didn’t see a profit. The epic had been popular since Italian filmmaker Giovanni Pastrone unveiled Cabiria in 1913 and by the 1920s some films were being produced on a massive scale, from the Hollywood epics of D.W. Griffith, Cecil B. DeMille and Erich von Stroheim to German visionary Fritz Lang’s Die Niebelungen (1924) and Metropolis (1928), the first great sci-fi drama. Lang was one of the directors associated with German Expressionism, one of the earliest influential film movements, whose play with light and shadow (chiaroscuro) would later prove influential over the film noir thrillers in post-war US.

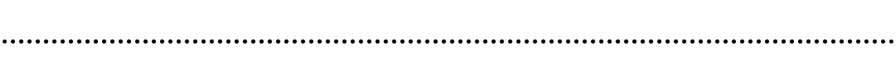

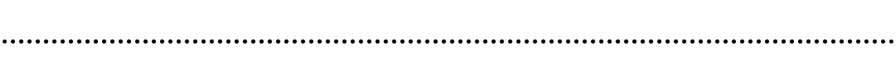

Alongside German Expressionism was the work of Soviet filmmakers such Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov, whose approach to editing—Soviet Montage—which understood that two shots with their own meaning could be joined together in a way to make a third meaning, was creating a different but no less influential kind of cinema. The Battleship Potemkin (1925) and Man with a Movie Camera (1929) best exemplified this. Both German Expressionism and, particularly, Soviet Montage would prove influential over the work of rising political forces in the 1930s, who saw in cinema the perfect propaganda machine.

Battleship Potemkin (1925)

For some film critics, the late 1920s witnessed cinema at its apotheosis. And the arrival of synchronous sound, which had long been experimented with but began to be rolled out following the runaway success of The Jazz Singer (1927), stunted the medium’s development. The requirements of rudimentary sound technology—its lack of sophistication—stunted camera movement. So, films like Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), F.W. Murnau’s rhapsodic, dazzling drama, gave way to films where visuals were more mundane. The arrival of sound also had a Tower of Babel effect. Whereas a film without speaking could be screened in any country with only the replacement of intertitle cards, sound in film limited what countries a film could be screened in. Dubbing and subtitling would compensate to some degree, and in more recent decades international titles have occasionally been successful, but outside the hegemony of English-language films, cinema lost its sense of being truly global.

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927)

Despite the physical limitations of sound, cinema increased in virtuosity throughout the 1930s and 1940s. Hollywood reigned supreme, enjoying its Golden Age. But other cinemas around the world revelled in success. France became one of the capitals of cinema, a position it has retained. India’s post-war years saw the rise of independent filmmakers who, like the equally daring Italian Neorealists, shone a light on areas of society previously unrepresented on the screen. Film was seen not only as a platform for entertaining audiences, but also a medium to inform and enlighten. Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955) became a landmark for its portrayal of poverty in rural Bengal, but remains essential viewing because of the warmth of its humanity. Likewise, Vittorio De Sica’s Neorealist classic The Bicycle Thieves (1948), a stark contrast with the films produced under the Fascists in the 1930s both in its setting—the streets of Italy and in focussing on the working class.

Pather Panchali (1955)

By the early 1950s, cinema had become the most popular form of entertainment around the world. To ask what cinema is to the average person at that time would likely have elicited the response, a form of escape, two hours in another world, or just a night out. But the era also introduced the first existential threat to the medium, which itself posed the question, ‘why cinema?’

That threat was television...

Come back next week to read Part 2 of this series. In the meantime, cinemas are back open!