If cinema’s first century saw the medium undergo radical transformation, the 1990s witnessed the digital revolution transform both the production and exhibition of films. The subsequent two decades continued this trend, with developing technologies widening available platforms for watching films, which some see as the beginning of the end – again – for the big screen. And if that weren’t enough, writes Ian Haydn Smith, for the first time in their history, cinemas all around the world were forced to close.

Digital technology transformed cinema at every level. Between the mid-1990s and 2000s, it would impact filmmaking, post-production, cinema exhibition and home entertainment. Just as the way people watched their choice of films at home switched from video to DVD, so too could filmmakers switch from analogue to rapidly developing digital filmmaking equipment. If the results at first proved less than impressive, increasing sophistication of both audio and visual technologies saw rapid developments.

Experiments in digital, or ‘electronic’ cinematography began in the early 1980s, with the development of metal-oxide-semiconductor (MOS) image sensors, followed by the introduction of the charge-couple device. There was little take-up at first, but by the mid-1990s, the economic benefits of shooting with digital, as well as the easy integration of visual effects in post-production, saw its popularity increase. Rainbow (1996), Bob Hoskins’ directorial debut, was shot on digital and featured extensive digital post-production, while The Last Broadcast (1998) is generally acknowledged to be the first feature to be entirely shot and edited using consumer-level digital equipment.

Rainbow (1996)

But it was George Lucas’ return to his Star Wars franchise that caused the biggest stir; The Phantom Menace (1999) featured sequences filmed with high-definition digital cameras, while the subsequent Attack of the Clones (2002) was filmed in its entirety with digital. As digital cameras have developed – some looking like little more than a computer with a lens – filmmakers such as Steven Spielberg, Christopher Nolan, Paul Thomas Anderson and Quentin Tarantino began to speak out in favour of filming on celluloid. But the cost-effectiveness of digital and its capabilities have found favour with the global film industry and has become the standard for many.

Editing followed suit. For decades, the process of piecing a film together involved the splicing of pieces of footage. But the release of Avid in 1987 transformed the industry. It would be followed in 1999 by Final Cut Pro. Although the 1992 comedy-drama Let’s Kill All the Lawyers was the first film to be edited digitally, it was Walter Murch’s Oscar-winning work on The English Patient (1996), which was edited entirely using Avid, that set the first landmark for the process. It was followed by No Country for Old Man, the Coen brother’s 2007 Cormac McCarthy adaptation, which became the first Best Film Oscar-winner to be edited (by the Coens, using the pseudonym Roderick James) on Final Cut Pro.

No Country For Old Men (2007)

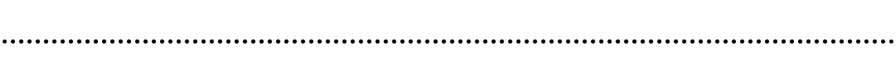

Cinemas were also swept up in the digital revolution. Image and sound were undergoing radical changes and by the early 2010s, most cinemas had transferred to digital projectors and only specialist or arthouse cinemas kept their 16mm and 35mm projectors. Sound had been in a constant state of improvement since Dolby first introduced the company’s Noise Reduction System in 1965. George Lucas entered the fray in the 1980s with THX, which vastly improved sound systems in cinemas and at home. By the mid-2010s, technologies such as Dolby’s Atmos system employed dozens of speakers to create an immersive aural world within cinemas.

Running alongside these innovations was a radical shift in how people accessed films they wanted to watch. And how they watched them. The introduction of TiVo opened up the possibilities of TV viewing. The arrival of streaming then multiplied the choices of films available to audiences. Whereas the arrival of video and then DVD gave people the chance to watch a film outside of the TV programming, streaming gave audiences near-unlimited choice without having to move from the comfort of their homes. Netflix quickly became the standard, while the number of streaming channels continues to increase, from large sites where films and TV programmes are dumped en masse, to the rise of curated platforms that offer a more bespoke menu of films.

Streaming services arrived just as smartphones and tablets were increasing in sophistication. Within a few years, it was possible to not only watch thousands of films at home, but if you had to go somewhere, you could continue watching as you walked down the street or took public transport. The big screen experience became a personal one, accessible 24 hours a day, from any location.

So where does that leave cinema? The coming of sound was seen by some as a threat to its existence. Television, then video and DVD also marked its end for some. But it endured. However, streaming is more pervasive than those earlier threats, so could it finally be cinema’s death knell? Then, in spring 2020, cinema shut its doors as the COVID-19 pandemic took effect. Some companies turned to streaming platforms to release their films. In the case of Disney and Universal, they offered films that would have been major theatrical releases for a premium price, on top of whatever services audiences already subscribed to. In late 2020, Warner Bros went further, releasing a list of their major cinema releases that would appear simultaneously on a streaming platform and theatrically. It caused some debate, with many filmmakers upset by the decision. But it seemed to signal that cinema’s days were finally numbered.

Cinema has proven itself to be a resilient medium over its 125-year existence. It has weathered many threats and storms. The latest challenges will likely see a larger number of people feel they can get the same experience from their home entertainment system that they could from a trip to their local cinema. And with many films that may be true – home entertainment systems, like cinemas themselves, have undergone significant advances. But no matter how we choose to watch a film, there will always be an appetite for the cinema. In the last few weeks alone, the audiences queuing up to see Chlöe Zhao’s Oscar-winning Nomadland in the cinema is a testament to the continued desire of some audiences to immerse themselves in the widescreen experience.

Cinema, like every art form, will constantly undergo change. It would likely be dull if it didn’t; like any genre, we would soon tire of it if it didn’t constantly attempt some kind of transformation or reinvention. But even with the events of the last year, any talk of its demise is premature. It might not hold the same place across the cultural landscape, but it remains essential, not only as entertainment, but also as a mirror that shows us who we are, and can even, at times, show us where we’re heading.