The use of songs and pre-recorded music has been a constant in cinema, going all the way back to the first major ‘talkie’, The Jazz Singer (1927). Some films use it to identify a particular era, while others make it part of the film’s USP, for example the theme song that helps advertise a new release to music listeners. The best films use tracks in an inventive way, adding to atmosphere, tonal range or visceral pleasure. The 19 films in this list rank among the most inventive in their use of a soundtrack.

The Glenn Miller Story (1954)

Something of an oddball, sentimental film for star James Stewart and director Anthony Mann at this point in their careers. A biopic about the celebrated band leader, who went missing when his plane purportedly crashed into the English Channel in 1942, it was made during the pair’s celebrated run of uncompromising, morally dark Westerns, such as Winchester ’73 (1950), The Far Country (1954) and The Man From Laramie (1955). It was also made in the same year that Stewart worked with Alfred Hitchcock on the thriller Rear Window. Nevertheless, Stewart’s boy-next-door persona, which made films like You Can’t Take It With You (1938), It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) and Harvey (1950) so memorable, stands out. No less a draw is the collection of wall-to-wall Miller hits. ‘In the Mood’, ‘Pennsylvania 6-5000’, ‘Chatanooga Choo Choo’, ‘Little Brown Jug’ and the achingly romantic ‘Moonlight Serenade’ helped create one of the best movie soundtracks.

The Graduate (1967)

Mike Nichols’ The Graduate defined an era. It appeared in cinemas just as parts of the US were embracing a growing counterculture and heading towards 1968’s Summer of Love. The film’s protagonist, Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman), is no rebel. He is the all-star track-and-field athlete beloved by his affluent middle-class WASP parents and their friends. But he is suffocated by their lifestyle and his act of rebellion – sleeping Anne Bancroft’s equally dissatisfied wife, the Braddocks’ family friend – ruptures the fabric of this world. Rather than draw on a variety of anti-establishment tracks from the era, Nichols approached Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel. Their soundtrack, comprising previously released tracks (a remixed ‘The Sound of Silence’, ‘April Come She Will’ and ‘Scarborough Fair’) and originals (including the now ubiquitous ‘Mrs Robinson’) perfectly encapsulates Benjamin’s desire to escape.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1969)

The soundtrack that was never meant to be. Acclaimed composer Alex North (The Misfits, 1961; Cleopatra, 1963) had been commissioned by Stanley Kubrick to write the film’s score. While filming his space epic, Kubrick, like many other filmmakers, used a temp track – a temporary soundtrack used to get a sense of a film’s pace or tone. He eventually decided that this pre-composed soundtrack would be perfect. It is. From Richard Strauss’ ‘Also sprach Zarathustra’ and Johan Strauss II’s ‘The Blue Danube’ waltz to the unnerving sounds of György Ligeti’s ‘Requiem’, ‘Lux Aeterna’ and ‘Atmosphères’, these tracks bring majesty to the film.

Trouble Man (1972)

Marvin Gaye had gone from being a star of the soul-music scene to political troubadour with his 1971 album What’s Going On. He wanted more control of his sound and, on agreeing to come up with a soundtrack for Ivan Dixon’s Blaxploitation film, was given complete artistic freedom. It remains only one of two albums that the artist solely wrote and produced. There was pressure on Gaye to continue a winning formula that had been set for Blaxploitation soundtracks – Isaac Hayes and Curtis Mayfield had scored major successes with their work on Shaft (1971) and Superfly (1972). Gaye didn’t disappoint. His album may be less well known today, but it remains a rich trove of grooves from the era. More recently, in Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014), when Anthony Mackie’s Sam Wilson first encounters Chris Evans’ Steve Rogers while out running near the Washington Monument, the soon-to-be Falcon tells Captain America, ‘Marvin Gaye, 1972. Trouble Man soundtrack. Everything you missed, jammed into one album’. There’s a sense that Gaye was trying out different ideas on every track. And when an average Marvin Gaye idea is a great listen, it hints at what a mostly unsung gem this soundtrack is.

American Graffiti (1973)

The vast soundtrack that populates George Lucas’ evocative portrait of youth culture in early 1960s California became the template for subsequent ‘Love the movie? Buy the soundtrack’ releases. (It exploded in the 1980s, with Flashdance [1983] Top Gun [1986] and 1987’s millions-selling Dirty Dancing.) By some distance Lucas’ best film as a director, American Graffiti is a euphoric exercise in retrofitted nostalgia. Notwithstanding the excellent performances by its ensemble cast – including Richard Dreyfuss, future director Ron Howard, Harrison Ford, Candy Clark, Charles Martin Smith, Paul Le Mat, Kathleen Quinlan and Cindy Williams – the film would pale without its vast collection of songs from the era. The accompanying album proved such a success, it spawned a sequel that only featured one track from the film, but its ‘inspired by’ USP would become a staple of future film-soundtrack releases.

Mean Streets (1973)

Few directors have employed songs to such thrilling effect as Martin Scorsese (his use of The Rolling Stones’ ‘Gimme Shelter’ in Goodfellas [1990], Casino [1995] and The Departed [2006] is simply iconic). Just watch the opening of his 1973 breakthrough. We see Harvey Keitel wake up from a nightmare. He washes his face then heads back to bed. As his head lowers onto the pillow, Scorsese employs a jump cut, fracturing the reality of the world we’re watching and replacing the sounds of the city – the constant police sirens – with The Ronettes’ ‘Be My Baby’, Phil Spektor’s Wall of Sound production amplifying the music and jolting us. Later, when Robert De Niro’s Johnny Boy gets his proper introduction, we see him walk into the bar he and his friends frequent, trouser-less, accompanied by two women, to the strains of The Rolling Stones’ ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’. These two sequences alone guarantee Mean Streets a place on the list.

Saturday Night Fever (1977)

An essential soundtrack, the Bee Gees’ songs propelled John Badham’s portrait of a working-class Italian-American (John Travlota in a star-making turn) desperate to shake off the confines of his drab everyday life on the dancefloor. It’s a surprisingly bleak and violent film, which refuses to portray Travolta’s character Tony Manero as a working-class hero. But for all the film’s grittiness, the euphoria of the Bee Gees’ music shines through. There are other tracks: ‘Boogie Shoes’ by KC and the Sunshine Band, ‘Disco Inferno’ by The Tammps and Kool & the Gang’s ‘Open Sesame’. But they’re eclipsed by ‘Stayin’ Alive’, ‘Night Fever’, ‘More Than a Woman’ (also covered well by Tavares), ‘Jive Talkin’’, ‘How Deep Is Your Love’ and ‘You Should Be Dancing’.

Purple Rain (1984)

Let’s be clear, this is not a Best Film list. Because this is not a good film. Yes, it’s better than Prince’s subsequent efforts, the charm-free Under Cherry Moon (1986) and god-awful Graffiti Bridge (1990). But when it comes to feature-length films, most Prince fans – and any sane human being – would probably rather watch his stunning 1987 concert film Sign ‘o’ the Times. However, there’s no denying the monumental, era-defining power of the soundtrack that accompanies this film. 1980’s ‘Dirty Mind’ had already established Prince as one of the most promising talents of the new decade, while 1982’s ‘1999’, the first to be released with his band the Revolution, pushed him further into the mainstream. But ‘Purple Rain’ made him a superstar. The film was intended as a semi-fictional, mythic account of his rise. It remains, at best, a footnote to a career that happens to have one of the greatest soundtracks ever produced.

The Breakfast Club (1985)

The film that transformed Simple Minds’ ‘Don’t You Forget About Me’ from an original song on the soundtrack to the anthem of a generation, John Hughes’ drama about a disparate group of students forced to spend Saturday detention together remains one of the greatest teen movies ever made. (As far as ‘80s teen movies go, it’s arguably equaled only by Hughes’ 1986 comedy Ferris Bueller’s Day Off). Emilio Estevez, Molly Ringwald, Judd Nelson, Ally Sheedy and Anthony Michael Hall are the students. Paul Gleason is the inept teacher watching over them. They smoke, swear, bitch at each other, open up and finally find common ground – antipathy towards parents, teachers and those in charge. All the while, their antics are set to music by bands and singers who – Simple Minds excepted – have not fared as well as the film, but at the time felt essential to any schoolkid who identified with one of Hughes’ characters.

Do the Right Thing (1989)

Spike Lee’s brilliant, incendiary film opens with an electric credit sequence. Branford Marsalis’ lyrical sax playing comes to an end with the appearance of the film title and is replaced by Public Enemy’s ‘Fight the Power’, one of the key tracks from their upcoming third album Fear of a Black Planet. It accompanies Rosie Perez’s confrontational dance moves – underpinning the provocative nature of the film. Elsewhere, tracks by artists like Steel Pulse, Teddy Riley, Al Jarreau, Take 6 and Keith John are interspersed with compositions by the filmmaker’s father, acclaimed jazz musician Bill Lee. But it’s PE’s song that stands out. Few films have combined music and image to such incendiary effect from the outset.

Reservoir Dogs (1992)

For some, there are movie soundtracks before and after Quentin Tarantino appeared on the scene. There’s no doubt that his eclectic and encyclopaedic knowledge of popular music – and the wider landscape of popular and pulp culture – informed his films. But the way they were integrated into his movies and, in return, the way his movies were enmeshed within a soundtrack, felt fresh. Take his electrifying debut. Reservoir Dogs stands alongside Sex, Lies and Videotape and Do the Right Thing (both 1989) in playing a significant role in rejuvenating independent US film. The film’s soundtrack features The George Baker Street Collection’s ‘Little Green Bag’, Blue Swede’s ‘Hooked on a Feeling’, Bedlam’s ‘Magic carpet Ride’, Harry Nilsson’s ‘Coconut’ and, of course, ‘Stuck in the Middle with You’ by Stealers Wheel. Tarantino interspersed comedian Steve Wright’s fictional radio host’s in-film interludes between the tracks, along with lines of dialogue from various scenes. The formula, though not original – the soundtrack to Good Morning, Vietnam (1987) did a similar thing with Robin Williams’ monologues from the film – proved effective. And the album became a hit.

Above the Rim (1994)

The East Coast rap scene might have hit the ground running early thanks to Public Enemy’s collaboration with Spike Lee. But the West Coast wasn’t far behind. And once labels like Death Row understood the marketing potential of an accompanying movie soundtrack, there was no stopping upcoming bands using cinema as a platform for promoting their work. One of the earliest – and best – examples is Jeff Pollack’s basketball drama, featuring one of the few excellent on-screen performances by Tupac Shakur. It tells the story of an up-and-coming basketball star, and his relationship with his two brothers: a washed-up basketball hopeful and a drug dealer. If the film is solid, the music is a key moment in the development of the hip-hop soundtrack. A collaboration between Death Row and Interscope Records, it was produced by Suge Knight, supervised by Dr. Dre and featured 2Pac, Snoop Dogg, Sweet Sable and a variety of the LA music scene’s abundance of talent.

Trainspotting (1996)

Danny Boyle’s kinetic, head-trip style of filmmaking found its perfect partner in Irvine Welsh’s 1993 novel. An account of the lives of a loose-knit gang of friends in Edinburgh, it details the impact of drink and drugs on their lives. From its opening chase sequence, with main protagonist Renton (Ewan McGregor in his breakthrough role) pursued by police, the film boldly offers up a portrait of the highs and lows of drug abuse. Throughout, Boyle employs an eclectic soundtrack, from Iggy Pop’s ‘Lust for Life’ and Brian Eno’s ‘Deep Blue Day’ (in that toilet sequence) to Lou Reed’s ‘Perfect Day’ and Underworld’s ‘Born Slippy’. But it was through the presence of Pulp, Blur and Damon Albarn that the film came to be seen as a key part of the Britpop movement that emerged in the mid-1990s.

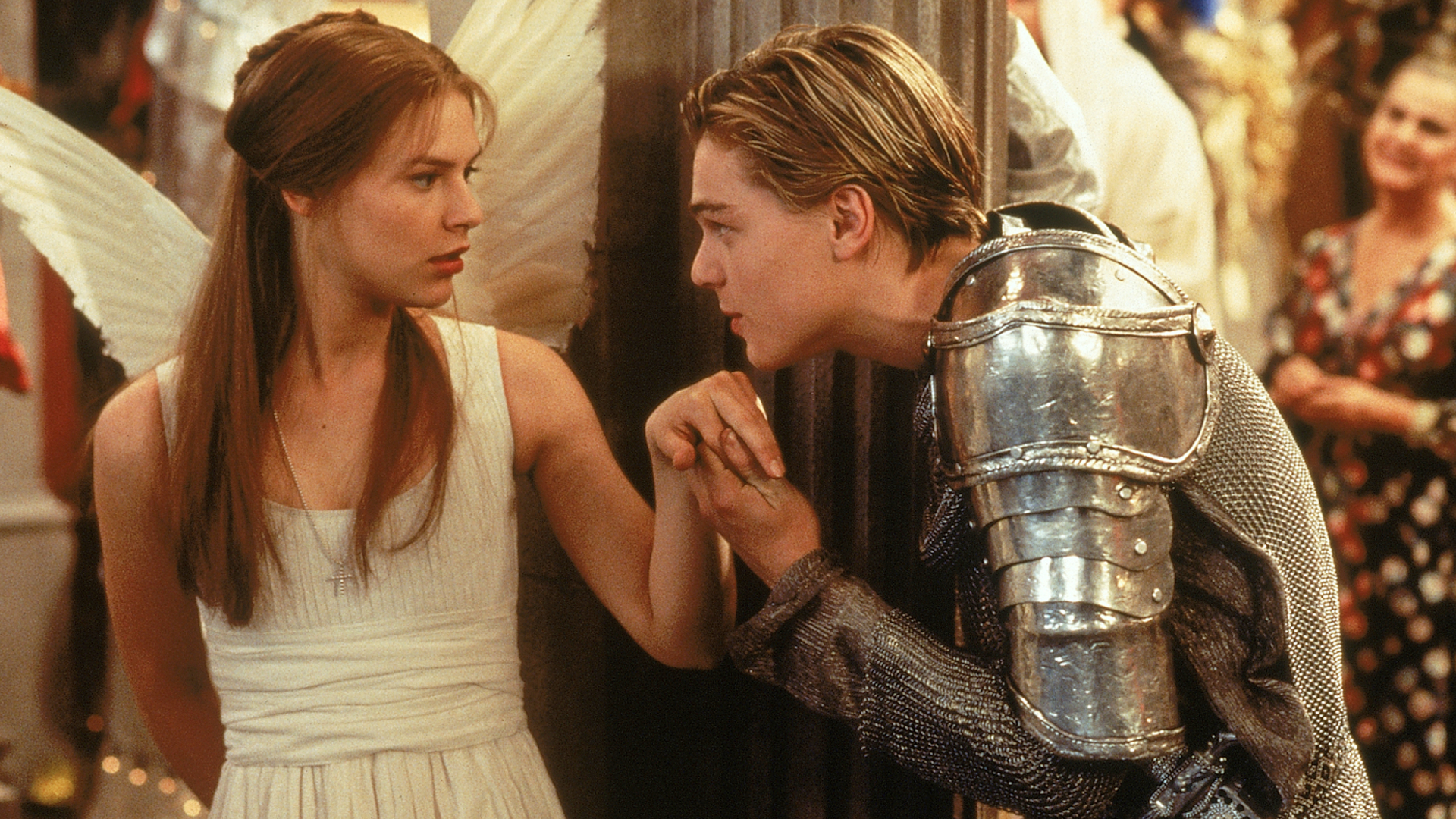

Romeo + Juliet (1996)

A soundtrack as exuberant, chaotic and enjoyable as the film it comes from, it finds The Cardigan’s monster hit ‘Lovefool’ going up against Kym Mazelle’s take on the 1976 Candi Station classic ‘Young Hearts Run Free’, while Quindon Tarver’s impressive cover of Rozalla’s ‘Everybody’s Free (To Feel Good)’ faces off against Radiohead’s ‘Talk Show Host’. There are also tracks by Garbage, Gavin Friday, Butthole Surfers and the Wannadies. Each song seems to exist in its own mood climate, but together they create a strange high that beautifully reflects the dizzying euphoria of Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes’ titular lovers.

Good Will Hunting (1997)

Some films find their heart through the use of a single performer’s songs. It worked for Mike Nichols, who included tracks from Damien Rice’s debut album ‘O’ for Closer (2004). But rarely has it been quite as effective as Gus van Sant’s reliance on Elliott Smith for Good Will Hunting. There are actually only five Smith tracks used in the film, but their effectiveness, particularly the melancholy ‘Between the Bars’, sets the tone of the drama and underpins its ‘indie’ feel. The soundtrack also features The Waterboys’ riotous ‘Fisherman’s Blues’ and Starland Vocal Bands’ ‘Afternoon Delight’ (a song that’s almost impossible to listen to with a straight face after watching the similarly titled episode in the second series of Arrested Development).

Boogie Nights (1997)

This is a film soundtrack as wallpaper. Individual songs may not stand out in the way Aimee Mann’s did throughout Paul Thomas Anderson’s subsequent Magnolia (1999), how Ella Fitzgerald’s ‘Get Thee Behind Me Satan’ does in The Master (2012), or David Bowie’s ‘Life on Mars’ in Licorice Pizza (2021). The songs in Boogie Nights, evoking the late 1970s and early 80s, better resemble Jonny Greenwood’s compositions for Anderson’s films, creating a layer of texture upon which the drama unfolds. That said, the synchronised disco sequence featuring The Commodores’ instrumental ‘Machine Gun’ is a classic Anderson moment – all one take and a stunning zoom. (It was recently rivalled by the disco scene in Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman [2018], which plays out to Cornelius Brothers and Sister Rose’s 1972 groove-infused ‘Too Late to Turn Back Now’.)

Almost Famous (2000)

It now seems odd to think that for a long time ‘Tiny Dancer’ wasn’t part of Elton John’s regular repertoire. Released on the singer-songwriter’s fourth studio album, at 6:12 minutes long, it was deemed too long for airplay at most radio stations. On its first release in the US, it only reached 41 in the charts. It didn’t even debut as a single in the UK. Then came Almost Famous. It’s a fictional version of writer-director Cameron Crowe’s teen life as a music journalist for Rolling Stone magazine. The band Stillwater is a composite of various musicians he hung out with. In a now iconic scene, the band, reeling from a major fallout, are together on their tour bus when ‘Tiny Dancer’ comes on the radio. Slowly, everyone sings along, healing any ruptures. There are more than a few other great songs on the album, from tracks by The Who, Simon & Garfunkel, Yes, The Allman Brothers Band, Led Zeppelin and David Bowie. But it's John’s track that shines through.

O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000)

Even by Coen Brothers’ standards O Brother, Where Art Thou? is an odd one. Inspired by Homer’s ‘The Odyssey’ and drawing on Preston Sturges’ classic 1941 comedy Sullivan’s Travels (the film-within-the-film is where the Coens got their title from), they came up with a prison-break film starring George Clooney, John Turturro and Tim Blake Nelson as chain-gang convicts whose sudden bolt for freedom finds them engaging with all walks of life and experiences, including a brush with fame as recording artists. The song they record, ‘I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow’, is just one highlight on an album, produced by T. Bone Burnett, that features bluegrass, country, gospel, blues and Southern folk music. The album became such a sensation that Burnett went on tour with it, taking with him a variety of performers, eventually producing the documentary concert Down From the Mountain (2000).

Marie Antoinette (2006)

Sofia Coppola may not have been the first director to give her film a soundtrack that contrasted wildly with its subject or the era in which its set. (Five years earlier, A Knight’s Tale had a medieval audience cheering Queen’s ‘We Will Rock You’ as aristocrats jousted.) But Coppola’s portrait of the ill-fated last Queen of France, based on Lady Antonia Fraser’s biography, was also a revisionist take on the iconic monarch. Coppola’s decision to accompany her character’s journey with tracks by Siouxsie and the Banshees, Bow wow wow, The Strokes, Adam and the Ants, The Cure, Gang of Four and New Order was a masterstroke, challenging the mostly conservative conventions of the costume drama.

Baby Driver (2017)

The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion’s ‘Bellbottoms’, the opener of their rip-roaring 1994 album Orange is not the sort of track you would expect to see in your average movie. But then, Baby Driver isn’t your average movie. A knowing take on the heist film, shot through with more than a little attitude, Edgar Wright’s cooler than cool story of a talented getaway driver trying to go straight is – almost literally – driven by its soundtrack. Aside from Spencer's chaos, there’s Bob 7 Earl’s classic ‘Harlem Shuffle’, Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers’ ‘Egyptian Reggae’, The Damned’s ‘Neat Neat Neat’ and Dave Brubeck’s incomparable ‘Unsquare Dance’. Wright is a pop-culture junkie and here the Shaun of the Dead (2004) and Hot Fuzz (2007) filmmaker let his tastes unfurl as Ansel Elgort’s driver tears up a city’s streets.

Cruella (2021)

Forget your Marvel and DC superheroes. If you want a smart, snarky, take-no-prisoners origin story, then look no further than this surprisingly dark take on one of Disney’s most popular antagonists. And the accompanying soundtrack works a treat. It not only helps define an era, but sets up the characters of Emma Stone’s titular antihero and her nemesis, played with joyous glee by Emma Thompson. It starts well with Florence and the Machine’s ‘Call Me Cruella’, before running the gamut, from Supertramp (‘Bloody Well Right’), Bee Gees (‘Whisper, Whisper’) and Blondie (‘One Way or Another’) to ELO’s ‘Living Thing’ and two cracking covers by Ike and Tina Turner, of The Beatles’ ‘Come Together’ and Led Zeppelin's ‘Whole Lotta Love’.

EXPLORE OUR LOST IN MUSIC COLLECTION ON CURZON HOME CINEMA