The most prestigious festival in the film calendar opens this week. But what makes Cannes so important, and why is it the best place for any international director to premiere their film? Here’s a quick explainer guide to the festival.

What is Cannes?

A city on the French Riviera, Cannes has become synonymous with glitz, celebrity and great cinema. When the world isn’t beset by a pandemic, it plays host to the international film festival every May. (It also hosts the Lions International Festival of Creativity, MIPCOM and MIPTV.)

The festival was created in 1939, with the French government deciding not to participate in the Venice Film Festival – which was founded in 1932 but had increasingly come under the influence of Benito Mussolini, having interfered in the 1937 edition to ensure that Jean Renoir’s anti-war drama La Grande Illusion did not win the top prize – instead announcing its own event. The Second World War stymied the festival for the next seven years, but it returned in 1946, which became known as the 1st Cannes International Film Festival.

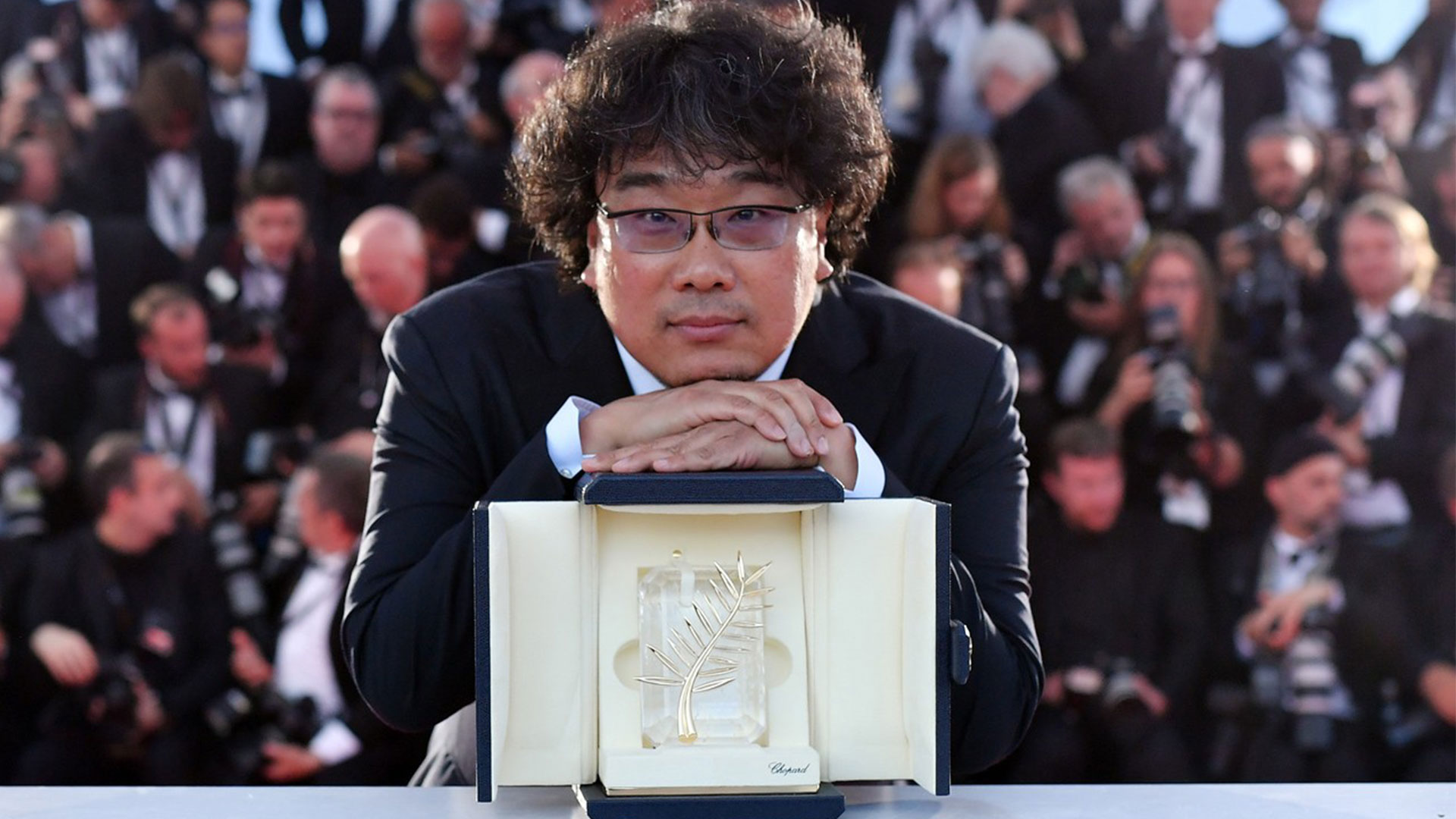

Cannes Film Festival 2019

With its backdrop of the French Riviera, it wasn’t too much of a challenge to attract major stars to the Croisette, the road that runs alongside the beach and where the Palais des Festivals – the main cinema, built in 1949, that hosts all the major premieres – is located. By the mid-1950s, with its alluring cocktail of sun, stars, sex appeal and nascent arthouse cinema scene, Cannes became the go-to festival for every major director. By the mid-1950s it had become the preeminent film festival, both for the quality of filmmaking on display and for the various scandals it generated.

Sophia Loren at the 8th Cannes Film Festival, 1955

The original prize was the Grand Prix du Festival International du Film. The first single film to win it was The Third Man in 1949. In 1955 the award’s title was changed to the Palme d’Or. Save for a decade from 1964 when it reverted back to the Grand Prix, it has continued to be the title of the festival’s top prize.

The Sections

At the festival’s close, the various juries announce the awards, and to the uninitiated, it can seem confusing. As the festival has expanded over the decades, it has separated out into various branches in order to encompass a wider scope of cinema.

Official Selection:

This is the main section of the festival and encompasses the major awards categories.

The main competition tends to feature the festival's big-hitters, all competing for the Palme d’Or. It’s where you find the established directors (the likes of Haneke, Campion, Almodóvar, Loach and Leigh) and the bright new lights who have worked their way through the other sections. (Mommy [2014] director Xavier Dolan being one of the brightest in recent years.) This year sees Mia Hansen-Løve, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Leos Carax, Sean Penn, Ildiko Enyedi, Catherine Corsini, Jacques Audiard, Mahamat Saleh Haroun, Asghar Farhadi, Paul Verhoeven, Bruno Dumont and a host of other world-class directors compete for the prize.

The Palme d'Or

Un Certain Regard runs in parallel to the Palme d’Or and was created in 1998. It offers an opportunity for work by young or daring filmmakers. It can also feature distinctive films that on occasion eclipse those films competing for the top prize. Recent examples include the popular Icelandic drama Rams (2015) and the uncategorisable Border (2018). 20 films will compete this year for the prize.

Un Certain Regard

The Short Film Palme d’Or, as its name suggests, is the top prize for short films and tends to feature around ten entries.

Short Film Palme d'Or

Cinéfondation supports the work of film students with a handful of short and medium-length films chosen from film schools around the world.

Cinéfondation

Alongside these strands are Out of Competition and Special Screenings. These tend to include titles that might look out of place in the competitions. (Hollywood blockbusters make a regular appearance as part of these selections.) There’s also the Cannes Classics, which supports the restoration and screening of older films. This has become more high profile since the creation of the World Cinema Foundation, which Martin Scorsese is a vocal supporter of and advocate for. And the Cinéma de la Plage gives the public the opportunity to watch Cannes Classics and Out of Competition films on the beachfront.

Cinéma de la Plage

Parallel Sections

Directors’ Fortnight was conceived in 1969 and has tended to align itself with more challenging fare. At the same time, it has thrown plenty of curveballs over the years. UK eyes will be focused on this strand as Joanna Hogg and Clio Barnard have their films competing for the award at this year’s festival.

Directors' Fortnight

International Critics’ Week first took place in 1962. It was organised by the French Syndicate of Film Critics and is now the oldest non-competitive strand of the festival. Its remit is to showcase the first and second features by filmmakers from around the world. Over the course of almost sixty years, it has a prodigious track record of recognising major talent, with the likes of Wong Kar-wai, Leos Carax, Jacques Audiard and Guillermo del Toro all having had their first films in this section.

International Critics' Week

The Business

Lest we forget that business often follows film, the festival also boasts the busiest film market in the world. As competition juries, critics and audiences settle in to watch the programmed films, thousands of delegates descend on the Marché du Film to sell their films or attract financing for upcoming projects. Founded in 1959, it is a hive of activity and an essential component in ensuring that there are always films to screen in the festival.

Marché du Film

No Cannes Do

Outside of the outbreak of the Second World War and a few cancelled early editions due to financing, Cannes has run like a well-oiled machine for 70 years. Well, save for two significant editions. The most recent was last year when the COVID pandemic saw a smaller-scale, online version rather than the usual behemoth. There was also the political turmoil of 1968, during which a group of filmmakers successfully brought the festival to a halt. That year, the festival opened with complaints from some filmmakers that the arts should fully support the student and workers’ strikes taking place across the country and protest the sacking of Henri Langlois, the outspoken director of the Cinémathèque Français. Then, a few days in, a group of filmmakers took to the stage at the Palais and successfully stopped that year’s edition from going any further.

1968 protests at the Cannes Film Festival

The Controversies

If there’s one thing Cannes is renowned for, it’s controversy. In the 1950s that was supplied by the appearance of female stars in summer wear, most notably a young Brigitte Bardot turning heads and attracting photographers as she posed on the Croisette. But as the years have passed by and cinema has tackled taboos, the main controversies have either taken place on the screen or at press conferences. That most notable example of the latter took place in 2011, just prior to the screening of Melancholia, when Lars von Trier made – at best – a questionable attempt at humour regarding Hitler that saw him temporarily banned from the festival. (The film’s star Kirsten Dunst, who was sat next to the filmmaker when he made the comments, even attempted to stop him mid-flow, to no avail.)

Brigitte Bardot, 1955

As for the controversial films, here are ten of the most notable scandals at the Cannes Film Festival over the years:

1960 – A vintage year that saw Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita take the top prize and Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura was awarded with the Jury Prize. Fellini’s film caused angst amongst the Catholic community from the get-go, with its opening image of a statue of Christ being airlifted over Rome. While Antonioni’s film, now regarded as a landmark in cinema history, was derided by critics as dull, pointless and a creative cul-de-sac.

1961 – The Church were outraged again, this time by perennial provocateur Luis Buñuel, whose Palme d’Or-winning Viridiana was always destined to shock. A scathing critique of religious hypocrisy, Buñuel’s film is also blisteringly funny and, at times, visually dazzling.

Viridiana (1961)

1976 – The head of the main jury was celebrated playwright Tennessee Williams, whose comment ‘Watching violence on the screen is a brutalizing experience for the spectator’ went some way to expressing the disdain he felt at having to award the Palme d’Or – by a majority decision – to Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. The film has lost none of its power in the 45 years since its premiere, but it has long been acknowledged as one of the indisputable masterpieces of the New Hollywood that emerged in the late 1960s.

1989 – Steven Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies and Videotape won the Palme d’Or. It was a decision many agreed with. But not Spike Lee or supporters of Do the Right Thing, his searing account of racism in present-day New York. An exploration of onanism by some white dude beating a film that tackles the epidemic of prejudice and race-motivated violence made for one of the more interesting discussions regarding the role of cinema in society.

Do The Right Thing (1989)

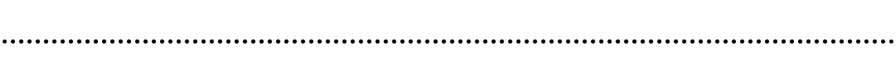

1990 – There were many who felt that David Lynch deserved Cannes’ top prize for his brilliant post-mortem of the American Dream, Blue Velvet (1986). Instead, he won it for Wild at Heart and judging by the reaction of the audience following the film’s premiere, and when the Palme d’Or winner was announced, a lot of people were not happy about it. But Cannes has long had a reputation for audiences expressing their opinion after – and, on a rare occasion, during – a screening. In recent years, there was Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (2006), Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life and Julia Leigh’s Sleeping Beauty (both 2011), Nicholas Winding Refn’s Only God Forgives (2013) and Gus Van Sant’s Sea of Trees (2015). Lynch even managed to repeat his Wild at Heart controversy when he premiered the prequel to his celebrated TV series Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992). Are any of these films that bad? No. (Well, the Van Sant comes close.) The boos are all part of the cinematic pantomime that is Cannes.

Wild at Heart (1990)

1996 – Crash – and we’re not talking Paul Haggis’ Oscar winner here – is not the most controversial film David Cronenberg has made. But like the J.G. Ballard novel upon which it’s based, there’s something combustible about the story’s combination of sex and automobiles. It’s not even the most explicit film in the festival’s history. But it screened during a visit to the festival by British Secretary of State for National Heritage Virginia Bottomley, who expressed her outrage that the film was a British co-production. But then it emerged that all her ire was directed at a film that she hadn’t actually seen. But that was enough to see it become one of the must-see films of the year.

2002 – There’s no denying the cinematic flair and emotional power of Gaspar Noé’s Irreversible. But it’s hard to stomach the 12-minute, single-shot rape scene that takes place in it (along with a shocking act of violence before it). It’s possible to justify the sequence by arguing that no scene of sexual violence should be ‘watchable’. But a counter to that would be why show the scene at all. Debates like that surrounded the film long after its appearance at the festival. And Noé has continued to court controversy, but never with the same furore that he amassed for this deeply disturbing film.

Irreversible (2002)

2003 – Is it real? Or is it a prosthetic? That was the question regarding the fellatio scene between Chlöe Sevigny and Vincent Gallo in The Brown Bunny. Another reason this may have become the talking point around the film is that there was little else to recommend the crushingly disappointing second feature by the actor-turned-director of the inventive, irreverent Buffalo 66 (1998). Gallo later apologised for the film, but his reputation as a director has never quite recovered.

2009 – It has an opening scene featuring unsimulated sex. It deals with the horror of a grieving couple, played by Charlotte Gainsbourg and Willem Dafoe, who commit unspeakable acts of violence on each other. It’s directed by Lars von Trier, and it’s called Antichrist. Of course, it was going to be controversial. But who’d have guessed that so much of the conversation would revolve around a talking fox?

Antichrist (2009)

2013 – Blue is the Warmest Colour

In a rare and deserved act of generosity and because a film in the competition can only win one award, Jury President Steven Spielberg and his colleagues not only awarded the Palme d’Or to Blue is the Warmest Colour director Abdellatif Kechiche, they also awarded it to the film’s lead actors Léa Seydoux and Adèle Exarchopoulos. Their performances take us through the arc of a relationship, from the early, heady moments of infatuation, through the physical intensity of their attraction, through to the shifting gears of a long-term relationship and the messiness and pain caused by its end. But no sooner had the film premiered that word began to spread about Kechiche’s direction of the actors during the lengthy sex scene and also the source graphic novel’s author Julie Maroh’s displeasure with that sequence. Nevertheless, it is impossible to overstate the brilliance of Seydoux and Exarchopoulos performances.

Blue is the Warmest Colour (2013)

Discover our Cannes collections on Curzon Home Cinema