Since the Academy Awards began in 1929, Hollywood has bestowed its highest honour upon all manner of movies, from comedies to westerns, musicals to dramas. Here, we run down our favourite Best Picture winners of all time.

Wings (1927)

The first Academy Awards ceremony – created by studio boss Louis B Mayer and covering films released between 1927 and 1929 – were held during a private dinner at LA’s Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel. The 270 guests paid $5 ($70 today) for a ticket and the awards part of the evening lasted just 15 minutes. (How times have changed!) There were only 12 categories and a mere three Best Picture nominees: Frank Borzage’s romance 7th Heaven, Lewis Milestone’s crime thriller The Racket and William A Wellman’s World War I drama Wings. Wellman’s film won. Its combination of epic scale, technical virtuosity and more than a little emotional manipulation set the template for many a future winning film. It still looks impressive today.

It Happened One Night (1934)

The start of a five-year run of Oscar successes for Frank Capra, this perfect vehicle for Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert is one of only a handful of comedies to bag the Best Picture Academy Award. Not only that, it remains one of just three films – along with All About Eve (1950) and The Silence of the Lambs (1991) – to win the Big Five (Picture, Director, Screenplay, Actor and Actress). Combining romance, social commentary and screwball comedy, Capra’s film is all charm and rakish mischievousness, largely thanks to Robert Riskin’s near-perfect screenplay. Gable and Colbert dazzle as the odd couple who eventually fall in love, and the film features a series of wonderfully conceived set pieces, including the ‘wall of Jericho’ bedroom scene.

Gone with the Wind (1939)

Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 novel was a huge bestseller, and producer David O’Selznick’s film adaptation remains one of the highest-grossing films of all time. However, both works reflect the era they were made in and their racial politics are now regarded as regressive at best (it’s no surprise that Spike Lee used a sequence from the film in his 2018 satire BlacKkKlansman). So why include the film here? In terms of craft, Gone with the Wind exemplifies the pinnacle of classical Hollywood. Its production history is fascinating, particularly the casting of antiheroine Scarlett O’Hara – a search for a star that finally saw Vivien Leigh take the role. But mostly, the film warrants seeing because of Hattie McDaniel. She became the first Black actor to win an Academy Award, and her knowing performance undercuts whatever motivations were driving the film. And yet, come Oscar night, when her name was announced, it took an inordinately long time for McDaniel to reach the stage and accept her award because she had been relegated to the back of the auditorium.

Casablanca (1943)

Like Gone with the Wind, Casablanca was less the creation of its director Michael Curtiz, than one moulded by its wunderkind producer Hal B Wallis. He navigated the script through a series of writers, also welcoming some ad-libbing from star Humphrey Bogart. The actor had previously been known as a regular in gangster films, and it was Wallis who saw something different in him, ordering Bogart not to wear a hat unless he had to as a way of distancing him from previous roles. Ingrid Bergman, for her part, added European sophistication. When the civilians populating Rick’s Café sing ‘La Marseillaise’ in the face of their Nazi oppressors, there were real tears on display, since most of the people present had escaped persecution in Europe. Casablanca is both hard-edged and unashamedly romantic. When the Best Picture award was announced, studio head Jack Warner jumped on stage to accept it. Wallis was furious and left Warner Bros to become a successful solo producer. But Casablanca remains his finest achievement.

All About Eve (1950)

If someone created an illustrated dictionary with a specific film representing each word, All About Eve would appear under ‘waspish’. Joseph L Mankiewicz’s theatre-world drama is a film in love with language and the wit derived from it. The characters are venal, narcissistic and frequently cruel. But as a spectator sport, All About Eve is the grey-matter equivalent of a gladiatorial bout. Bette Davis rules the roost as star du jour Margot Channing. But her position atop of Broadway is challenged by Anne Baxter’s Eve Harrington. At a post-show soirée, Margot seems to be the only person who can see the ambition behind Eve’s innocent façade, and the threat she feels makes her even more dangerous. Davis is at the top of her game, matched by an excellent cast that includes Baxter, Celeste Holm, George Saunders and Marilyn Monroe in an early role. It walked away with the top five Academy Awards. That’s no mean feat, as it was up against Billy Wilder’s equally bleak evisceration of Hollywood, Sunset Boulevard.

On the Waterfront (1954)

A film about betrayal by a filmmaker accused of turning his back on his peers. Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront is set in the world of corrupt union bosses and the criminal-gang infiltration of New York’s docks. Marlon Brando is sensational as a boxer who gave up his chance in the spotlight when he threw a fight and is now relegated to being a heavy. But rage and regret see him rebel against the corrupt forces around him. Kazan had been one of the Hollywood figures who gave names to the House Un-American Activities Commission, who were investigating the Communist influence across American culture. Kazan continued his career unabated, but many never forgive him for his actions. On the Waterfront seethes with the wretchedness of the threat anti-Communist zealots forced so many people to face and the film ranks alongside Arthur Miller’s 1953 play The Crucible as a searing indictment of persecution.

Ben-Hur (1959)

There’s epic cinema and then there’s William Wyler’s Ben-Hur. The first film to win a record 11 Academy Awards, the biblical drama is big in every way. It was projected on the massive screen ratio of 2.76:1, employing 70mm lenses and 65mm film stock. It is 212 minutes long. It employed tens of thousands. And at its centre was the larger-than-life figure of Charlton Heston. The chariot-race sequence, filmed in Rome’s legendary Cinecittà Studios, remains one of the most extraordinary physical (i.e. real set, real people, no CGI) productions in cinema history, and the actions that unfold during it are still breathtaking. The film is now also famous for its homoerotic subtext. In particular, a javelin-throwing scene between Heston and fellow actor Stephen Boyd. It was written by Gore Vidal, and Heston was apparently unaware of the implied relationship between the titular hero and childhood friend Messala. Today, it appears as obvious as the oysters versus snails conversation between Tony Curtis and Laurence Olivier’s characters in Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960).

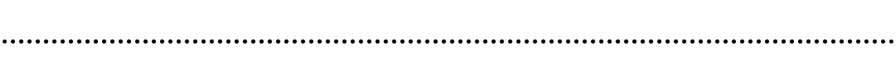

West Side Story (1961)

Four musicals won the Best Picture award in the 1960s. And if My Fair Lady (1964), The Sound of Music (1965) and Oliver! (1968) resembled the classical Hollywood musical, Robert Wise’s take on Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim’s Romeo and Juliet update was anything but. On the Town (1949) might have already played out as a whistle-stop journey through Manhattan, but West Side Story was working in a radically different register. As evinced by the aerial shots of New York’s tenement blocks at the beginning, this was a grittier kind of film. Yes, it’s still an all-singing and all-dancing portrait of life, but it was unlike any musical that had come before. It had an edge.

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

Few directors have mastered the art of telling an intimate story on the grandest of scales as David Lean, and Lawrence of Arabia ranks as the finest of his later, big-budget films. The story of TE Lawrence’s extraordinary adventures amongst Bedouin tribes before and during World War I, it was a shoo-in for the top award. (The film was up against The Longest Day, The Music Man, Mutiny on the Bounty and To Kill a Mockingbird.) Lean had previously won in this category with The Bridge on the River Kwai in 1957, but even by the standards of that large-scale World War II drama, Lawrence was immense. And yet, for all the film’s stunning sequences, it was Lean’s skill – along with Robert Bolt and Michael Wilson’s impressive screenplay, and Peter O’Toole’s performance – in delving into his protagonist’s conflicted psyche that made the film so rewarding.

Midnight Cowboy (1969)

The first X-rated film to win an Academy Award, Midnight Cowboy joined In the Heat of the Night, Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate (all 1967 Best Picture nominees), Point Blank (1967), Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and Easy Rider (1969) as part of a new era in Hollywood film. British filmmaker John Schlesinger’s drama was unrestrained in its portrayal of sexuality and the underbelly of life in New York City. The film’s despair may have been offset by John Barry’s winsome score and Harry Nilsson’s performance of Fred Neil’s ‘Everybody’s Talkin’’, but there was no mistaking the dark tone of the film. And its leads, John Voigt and Dustin Hoffman, were also part of this new, unrestrained filmmaking world.

The Godfather Part II (1974)

There are two camps when it comes to Francis Ford Coppola’s magisterial mafia epic: those who think The Godfather (1972) is the crowning achievement and those who prefer its darker follow-up. Essentially, the films work best combined, but The Godfather Part II exists in that rare universe where a sequel – of sorts – is regarded by some as superior to the original. The first film ended with Michael Corleone (Al Pacino, rarely better than he is across these films) selling his soul to the devil. In Part II, he ostensibly becomes the devil himself. It might be the bleakest Best Picture winner ever. It is also a complex exploration of morality, family and criminality at the heart of politics and society. The flashback sequences add context, showing us how Vito Corleone rose to the top of a crime family – with Robert De Niro giving a charismatic, Oscar-winning performance delivered almost entirely in Italian. But it is Michael’s journey to hell that gives the film its real power.

Amadeus (1984)

One of the key figures of the Czech New Wave, which stormed European cinema in the 1960s, Miloš Forman made a successful transition to Hollywood in the 1970s. His first feature there, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), remains one of three films that have one the five main Academy Awards. He then turned in respectable adaptations of the musical Hair (1979) and EL Doctorow’s novel Ragtime (1981) before achieving Oscar success again with his sumptuous take on Peter Schaffer’s story of the rivalry between Mozart and the less popular composer Antonio Salieri. Forman had assembled two potential casts from either side of the Atlantic. If he had gone with a British cast, Kenneth Branagh would have played Mozart, but he opted for the US ensemble. Tom Hulce is a livewire in the lead, apparently channelling John McEnroe’s mood swings, while F Murray Abraham walked away with the Best Actor Oscar for his stentorian portrayal of Salieri. Like the 1987 Best Picture winner The Last Emperor, Amadeus has all the trappings of a respectable Hollywood prestige production. But both films succeed because of their subversive elements. Like Forman’s early, anti-establishment films, his and Shaffer’s take on the life of Mozart is irreverent, scabrous, crude and earthy. It is also a masterclass in filmmaking.

The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

It took 64 editions of the Academy Awards for it to finally reward one of the most financially lucrative and popular genres: horror. And although Jonathan Demme’s film displays all the trappings of a prestige production, it is at its heart a stalker movie, that most quintessential of grindhouse favourites. Only the third film in the history of the awards to win all five top categories (with Ted Tally adapting Thomas Harris’ runaway bestseller), The Silence of the Lambs is so effective because of the artistry in every department. Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins are at the top of their game and their contrast in style informs everything else about the film. Foster’s Clarice Starling is ruthlessly modern, as is the world around her. Hopkins’ Hannibal Lecter is Gothic personified, which is reflected in the facilities that hold home, from the cave-like cell early in the film to the ornamental ‘bird cage’ that he eventually escapes from. The Buffalo Bill character caused controversy, with accusations of transphobia tarnishing the film. But it remains a stunning psychological chiller.

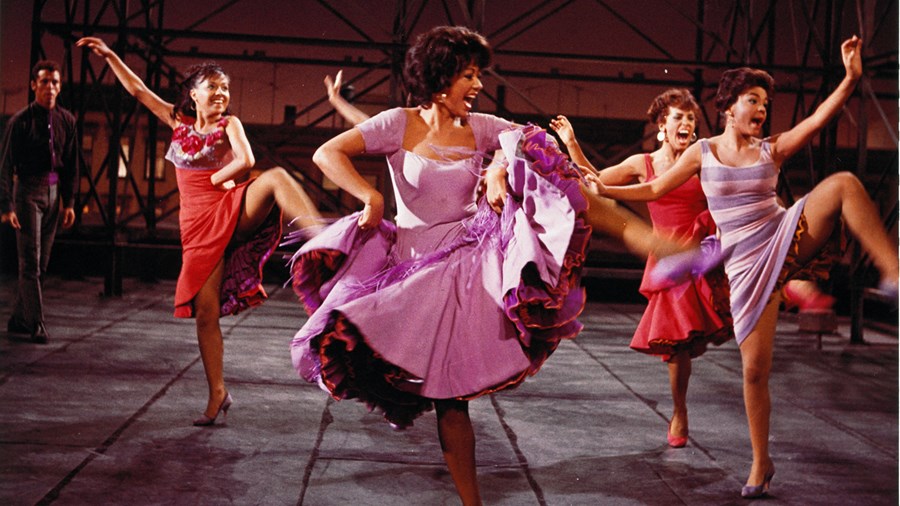

Unforgiven (1992)

Considering its status as the all-American genre, the western has only won three of the 90 something Best Picture Academy Awards. There was Cimarron in 1930 and Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves in 1990. Two years later, Clint Eastwood won with his elegiac portrait of life of the frontier towards the end of the 19th century. Second only to John Wayne as the genre’s most iconic figure, Eastwood drew on his experience working with Sergio Leone (on the Dollars trilogy) and Don Siegel (with whom he made five films, including the 1971 police procedural Dirty Harry) to produce a film that deconstructed the myth of the Manichean West. In playing William Munny, Eastwood acknowledged the brutality behind the heroic image of the genre.

Schindler’s List (1993)

Steven Spielberg finally entered the pantheon with his stirring drama about the actions of Oskar Schindler during World War II, despite being initially on board as a producer only. He offered the project to Roman Polanski, Sydney Pollack and Brian De Palma. Even Hollywood veteran Billy Wilder expressed an interest. But when he approached Martin Scorsese to direct, Spielberg realised, ‘I'd given away a chance to do something for my children and family about the Holocaust.’ So, he offered Scorsese Cape Fear (1991) instead and set about making Schindler’s List himself. Like his subsequent Saving Private Ryan (1997), for which he won Best Director (Shakespeare in Love was voted Best Picture), Spielberg’s Holocaust drama is a film of searing power with moments of his signature sentimentality. If the first half of the film is its best, the brilliant screenplay, an impressive ensemble cast and the filmmaker’s technical virtuosity keep it enthralling.

Titanic (1997)

The mid-1990s saw a comeback of the period epic at the Academy Awards. First Mel Gibson won big with his William Wallace adventure Braveheart (1995), Anthony Minghella followed suit in 1996 with his sumptuous The English Patient. And then James Cameron plunged us into the world’s most famous ocean liner with Titanic, which won a record-tying 11 Oscars with its era-defining tragic love story between the vagabond third-class passenger Jack Dawson (Leonardo DiCaprio) and high-society first-class girl Rose DeWitt Bukater (Kate Winslet), who must fight for survival on the doomed ship. Titanic was a record-breaking success of the highest order: it remained top of the box office for 15 straight weeks, was the first film to gross a billion dollars and its rousing anthem ‘My Heart Will Go On’ debuted at number one on the Billboard charts. DiCaprio and Winslet became global superstars thanks to their open-hearted performances and sizzling chemistry – who could forget the hand on the fogged-up car window? But Cameron’s film wasn’t always plain sailing, and its turbulent $200 million shoot was rabidly reported upon as a disaster waiting to happen throughout 1997, with articles on injuries and PCP-spiked chowder. Studio executives wanted the movie cut to two hours. Cameron refused. He was right. Audiences flocked to the film for its expert melding of historical drama, disaster movie and swooning romance. The majesty of Titanic’s scale is still a sight to behold, from the vastness of the engine rooms to the minute-by-minute account of the ship’s demise and the chilling fate of its passengers.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003)

Before The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies (2014), there was the film with infinite endings. There was little doubt that Peter Jackson’s epic three-part adaptation of JRR Tolkien’s classic fantasy would eventually win the Best Picture Academy Award and join Ben-Hur and Titanic as the most decorated Oscar winner. It certainly earned it with its huge box-office takings. But it was also a marvel of creativity and imagination. The realisation of Middle Earth is a stunning achievement, and one that has likely increased the coffers of the New Zealand tourist board. It may seem churlish to add a ‘but…’ here. But did we really need all those endings?

Slumdog Millionaire (2008)

Since his feature debut with the critically acclaimed Shallow Grave (1994), Danny Boyle has gained a reputation for the velocity of his style. Slumdog Millionaire is no less frenetic than Trainspotting (1996), but offers a more expansive worldview in telling the story of Jamal (Ayush Mahesh Khedekar/ Tanay Chheda/Dev Patel), from young homeless boy to potential winner of the Indian edition of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. Based on Vikas Swarup’s 2005 novel Q&A, Boyle’s film has a kinetic energy that drives the non-linear narrative at a furious pace, with Anthony Dod Mantle’s cinematography drawing out the extreme contrasts of Mumbai society. A commercial hit, Slumdog has also attracted significant criticism for its representation of India. But it’s impossible to deny the brio of Boyle’s adventure.

The Hurt Locker (2009)

A caustic anti-war drama or a film that revels in the excitement of a conflict-strewn world? The Hurt Locker divided critics with its ambiguous intentions, but few doubted the visceral power of Kathryn Bigelow’s tale of a bomb-disposal expert clinging on to his sanity on the front line of conflict. It deservedly made Jeremy Renner a star and delivers some breathtaking action set pieces. None more so than the film’s extraordinary opening, which sees Guy Pearce’s combatant realise too late that an IED has been detonated. However, the film’s most powerful – and telling – scene is one of its quietest. Returning home, Renner’s Staff Sergeant William James walks down a supermarket aisle populated with different varieties of cereal. Charged with placing his life on a precariously thin line when on duty, the banality of civilian life drives him back to doing what he does – and perhaps loves – best, leaving us to ponder whether life could ever be the same for anyone who has seen and experienced too much war.

Moonlight (2016)

Barry Jenkins’ portrait of three moments from the life of a young African American – as a boy (Little, Alex R Hibbert), teenager (Chiron, Ashton Saunders) and twentysomething man (Black, Trevante Rhodes) – is, by turns, sensual, erotic and exhilarating. Adapted from playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney’s story and featuring supporting performances by Janelle Monáe, Naomie Harris and Best Supporting Actor winner Mahershala Ali, Jenkins’ drama successfully conveys the intimacy of its subject’s journey alongside a wider exploration of identity. If that sounds heavy going, Moonlight is anything but. Jenkin’s prodigious talent – borne out in his subsequent If Beale Street Could Talk (2018) and the searing miniseries The Underground Railroad (2021) – and the skill of his talented cast draw out the story’s emotional power, leaving us to ponder the ramifications of the way these lives unfold.

Parasite (2019)

Only Donald Trump seemed unimpressed that a film not in the English language had finally won the Best Picture award at the 2020 Academy Awards. Bong Joon Ho’s masterpiece premiered at Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Palme d’Or (only the 1955 US melodrama Marty had previously won both accolades), and proceeded to bag every subsequent award it was nominated for. It had already won Best Original Screenplay, Best Director and Best International Feature awards on Oscar night, but there was something special about watching everyone’s reaction when Jane Fonda announced the Best Picture winner and the A listers in the auditorium clamoured for the telecast producers to turn the lights back on when the Parasite crew were being played off. A satire exploring social and economic inequality, Parasite felt like a film for the times, as well as riveting cinema.