Annie Ernaux – the Nobel Prize-winning author renowned for contemplative autofiction that delves into the intersection between gender, language and class – presents her 1970s home-video footage in the illuminating documentary The Super 8 Years. Co-directed by her son David Ernaux-Briot, the film, much like her books, braids the personal and the political, intimately exploring her own experience and placing it within the context of (inter)national events. At a special Lewes Depot screening, ahead of her sold-out Q&A with Sally Rooney at Charleston Literary Festival, she spoke through a translator about the meaning of truth, the lies of bourgeois happiness and how history shapes us all.

When writing the voiceover for the film – which frames your thoughts on the images we see – did you look back over your diaries from that period or conjure what happened from memory?

ANNIE ERNAUX: I did consult my diaries, they played an important part in scripting the film. In fact, at points, you hear my diaries being quoted. I think that was very important to me, because if I just rely on my memory, I tend to forget certain aspects of my past – things that hurt, insults that life has thrown at me – so I needed my diaries to recall those. At the same time, watching this footage reawakened certain memories that I’d lost for a while, so it was really interesting to explore things that hadn’t been recorded in my diaries. I see myself looking at this footage as though I was throwing a rock into a lake to see the ripples.

To what extent do you consider The Super 8 Years to be your then-husband Philippe’s story? It’s a portrait of him in a way, even though we hardly see him on screen at all.

AE: It’s his film any way you look at it. When I say it’s his film, of course I’m talking about the fact that the footage is his, he filmed it. But obviously I’m the one telling the story, it’s my voice you hear and so, in that sense, it’s my film and he’s in the background. I don’t think he would’ve liked the story I’m telling.

The film ends in 1981, when Philippe’s images run out as your marriage dissolves. Do you see this as a story of an ending or a beginning?

AE: I think that time is the subject of every narrative, ultimately. We’re trying to show certain events as being irreversible. But there’s also an added dimension: the fact that it’s silent footage. When you’re dealing with silent film, and with voiceover, there’s a wide gap that’s made really tangible. The gap between the time of the person doing the voiceover living now, and the time of the silent people who are seen in the images, who exist so far away. I think that adds a lot to the power of this film.

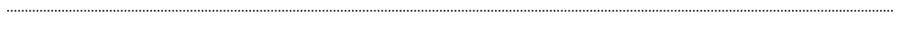

The Super 8 Years (2022)

Are you satisfied by the balance the film strikes between the intimacy of the home movies and the universality of the experiences presented?

AE: I was interested in looking beyond the superficiality of the images – and the habits and rituals of the family – to show what’s going on beneath that, showing other thoughts, other desires, and also to depict a certain historic moment with the arrival of Super-8 cameras. What was very important for me was to tell the story of a woman who’s finding that another path exists, another life is possible for her. The one regret that I have is that, at the time shown in the film, I was actually an activist. I was fighting for abortion rights for women in France, which was illegal back then. And so, looking now, I think perhaps it’s a shame that I didn’t find a way to include this in the film. But I think that if the film has any message, it’s showing, first of all, that another life is possible. It explores the wound that I experienced due to my [working-class] origins, living a happy bourgeois life, and I also wanted to show that all families – even if they’re not particularly important – exist in history. History shapes us all.

The Super 8 Years (2022)

Do you believe that the home movies presented in the film show the truth?

AE: Truth is a thorny issue. Of course, the footage you’re seeing has been selected, but it also came from a desire to preserve something real, to preserve moments of happiness. In a sense, the footage is a novel, the novel of a family, the story of a family. Does it have truth? Perhaps it can have the kind of truth that you find in fiction. In terms of my voiceover, the way I wrote the script for this film is very close to how I write my literary works. I’m always interested in digging beneath the surface, asking questions, going beyond what you can see. And so this creates a clash between the images and what I’m unveiling beneath them. But perhaps, in this clash, there is something real. There’s the story of our lives.

WATCH THE SUPER 8 YEARS IN CINEMAS OR ON CURZON HOME CINEMA